The Chicago police department runs a “black site” detention facility where detainees are “disappeared” and kept out of contact with family and lawyers at a warehouse on the city’s west side called Homan Square, according to a report published Tuesday by the London newspaper The Guardian. Stories of abuse at the “off-the-books” interrogation facility, where people are said to “vanish into inherently coercive police custody,” include:

• allegations of beatings by police, leading to head wounds;

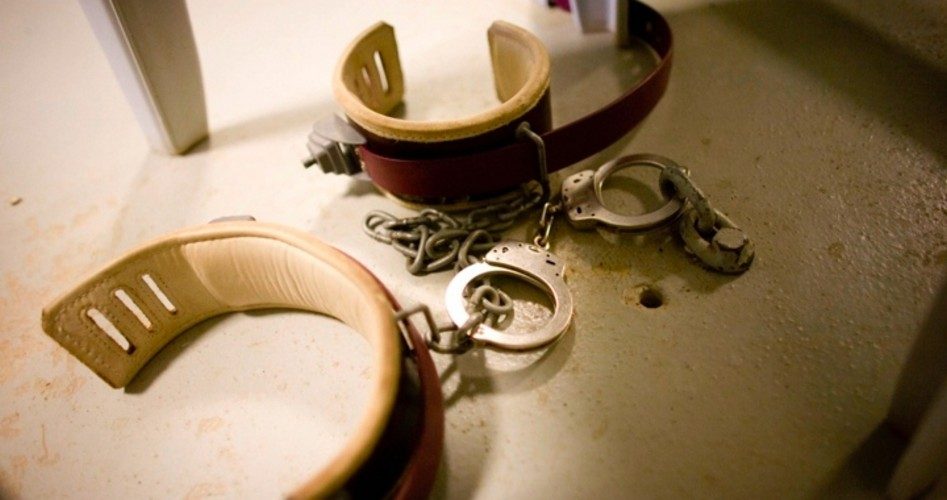

• shackling of detainees for long periods of time;

• holding people for up to 24 hours without access to a lawyer;

• keeping arrestees out of booking data bases.

“They just disappear until they show up at a district for charging or are just released back out on the street,” criminal defense attorney Anthony Hill told the Guardian. At least one man was found unresponsive in a Homan Square “interview room” and later pronounced dead, the report said, though the medical examiner said the cause of death was heroin intoxication.

“Homan Square is definitely an unusual place,” said Brian Jacob Church, one of the “NATO 3” arrested during a raid on protesters at the NATO summit in Chicago in May 2012. Church said he requested and was denied the opportunity to call an attorney during the approximately 17 hours he was held at Homan Square, all the while handcuffed to a bar behind a bench with his ankles shackled. He was interrogated intermittently during that time, without being informed of his Miranda right to remain silent.

Though the raid had attracted major media attention, a team of attorneys could not find Church through 12 hours of “active searching,” according to his lawyer, Sarah Gelsomino. No booking record existed, Gelsomino said, adding that it was only after she and others made a “major stink” with people in the offices of the city’s corporation counsel and with Mayor Rahm Emanuel that they even learned about Homan Square.

Church and his co-defendants were later taken to a nearby police station where they were booked on a number of charges, including conspiracy to commit terrorism and providing material support for terrorism. The three were accused of plotting Molotov cocktail attacks on city police stations, President Obama’s Chicago campaign headquarters, and Mayor Emanuel’s home. Defense attorneys at trial argued the men were drunken “goofs” who were duped into the plot by an undercover police officer who had infiltrated their group. In February 2014 a Cook County jury acquitted the men of the terrorist charges, while convicting them on two counts of misdemeanor mob action and two felony counts of possessing an incendiary device. Church spent two and a half years in prison (counting time served before trial) and is now out on parole. Recalling the long hours he spent in chains at Homan Square, he likened the facility to the secret prisons established by the CIA to interrogate suspected terrorists overseas.

“It brings to mind the interrogation facilities they use in the Middle East,” he told the Guardian. “The CIA calls them black sites. It’s a domestic black site. When you go in, no one knows what’s happened to you.” When taken to the warehouse, “I had essentially figured, ‘All right, well, they disappeared us and so we’re probably never going to see the light of day again,’” Church said.

Attorneys interviewed by the Guardian said Church’s experience at Homan Square was not an isolated or unusual incident. “It’s sort of an open secret among attorneys that regularly make police station visits, this place — if you can’t find a client in the system, odds are they’re there,” said Chicago lawyer Julia Bartmes. While a former Chicago police superintendent and a retired detective both told the Guardian that the police began using the warehouse in the late 1990’s, Chicago civil rights attorney Flint Taylor told the British newspaper that coercive tactics by the Chicago police have a far longer history.

“This Homan Square revelation seems to me to be an institutionalization of the practice that dates back more than 40 years of violating a suspect or witness’s rights to a lawyer and not to be physically or otherwise coerced into giving a statement,” Taylor said.

The Chicago police department did not respond to the Guardian’s questions about the facility, the newspaper reported, though after the story was published the department issued a statement denying any violations at the “sensitive” location, which is home to the department’s undercover units. The department “abides by all laws, rules and guidelines pertaining to any interviews of suspects or witnesses, at Homan Square or any other CPD [Chicago Police Department] facility,” according to the statement. “If lawyers have a client detained at Homan Square, just like any other facility, they are allowed to speak to and visit them…. There are always records of anyone who is arrested by CPD, and this is not any different at Homan Square.” The statement did not say, the Guardian noted, how long after an arrest or detention the records are generated or when they are available to the public. A department spokesperson did not respond to a detailed request for clarification, the paper said.

Eliza Solowiej of Chicago’s First Defense Legal Aid told the Guardian a former client had his name changed in the Chicago central bookings database before he was taken to Homan Square without any record of his transfer. She found out where he was after he was taken to the hospital with a head injury.

“He said that the officers caused his head injuries in an interrogation room at Homan Square,” Solowiej said. “He sent me a phone pic of his head injuries because I had seen him in a police station right before he was transferred to Homan Square without any.” The attorney said she had been looking for the man “for six to eight hours, and every department member I talked to said they had never heard of him.”

The Guardian’s report on Homan Square came only a few days after its two-part story about Chicago police detective Richard Zuley, who as a lieutenant in the Navy reserve was on special assignment at the U.S. detention facility on Guantanamo Bay, Cuba in 2003. According to a 2008 report of the Senate Armed Services Committee on the treatment of prisoners held by the United States around the world, Zuley wrote in a memo that military police dogs would be used in interrogating a blindfolded prisoner to “assist [in] developing the atmosphere that something major is happening and add to the tension level of the detainee.” The prisoner, Mohamedou Ould Slahi, recently published a memoir, Guantanamo Bay Diary, in which he described Zuley as a brutal and ineffective interrogator.

Tracy Siska, a criminologist and civil-rights activist with the Chicago Justice Project, said revelations about Homan Square show the lines between domestic law enforcement and overseas military operations are being blurred.

“The real danger in allowing practices like Guantánamo or Abu Ghraib is the fact that they always creep into other aspects,” Siska told the Guardian. “They creep into domestic law enforcement, either with weaponry like with the militarization of police, or interrogation practices. That’s how we ended up with a black site in Chicago.”

Photo at top shows shackles at Guantanamo: AP Images