Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Federalist Papers that: “[T]he practice of arbitrary imprisonments [has] been, in all ages, the favorite and most formidable instrument of tyranny.” This principle of constitutional liberty, when applied to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), reveals a frightening truth about the powers illegally granted the President in that legislation.

As has been recounted many times (never enough, however, given the urgency of the situation in which our Republic is now found) in this magazine and elsewhere, in various provisions of the NDAA, the Congress granted to the President the power to deploy the military of the United States to arrest and indefinitely detain American citizens inside or outside of the United States suspected by him (the President) of posing a military threat to national security.

Once the suspect is imprisoned, the NDAA authorizes the President to deny that person access to legal counsel (in defiance of the Sixth Amendment) and to refuse habeas corpus petitions requiring the government to inform the accused of the crimes with which he or she is being charged (in defiance of Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution). This latter deprivation of civil liberties, the one Hamilton described as tyrannical, is being challenged again by a man being held at the Guantanamo Bay Detention Facility.

Less than a month after President Obama signed the NDAA into law, lawyers for the government of the United States have cited that act as authority for the continuing detainment of Musa’ab al-Madhwani.

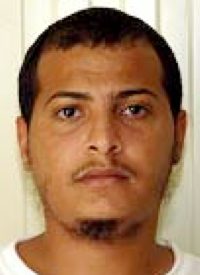

Al-Madhwani (pictured above) is a Yemeni national who has spent the last nine years in a cell at Guantanamo. After serving compulsory military service in Afghanistan after his visa and passport were confiscated, al-Madhwani traveled around the Middle East as a refugee, trying to get back home to Yemen. In 2002, he was captured in Pakistan by local police and soon was handed over to the custody of the U.S. military. After a stay in one of the CIA’s black site prisons where he says he was “brutally tortured” at the hands of his American captors, he was shipped off to Guantanamo, where he insists that the brutality continued.

Having spent nine years confined without knowing the laws he is charged with having broken, al-Madhwani has hired attorneys to compel the government to formally declare the charges against him or, alternatively, to release him. The record of the district court proceedings is enlightening and was published recently by RT.com:

In January 2010, US District Judge Thomas Hogan called 23 of the 26 documents that government presented as evidence against the man “tainted” because “coercive interrogation techniques” were used to obtain them. Judge Hogan would also rule, however, that the remaining three pieces of evidence were not. Even if months of torture in unimaginable conditions would cause al-Madhwani to admit guilt, the judge ruled that confessions offered up years later, which he viewed as “fundamentally different,” were enough to keep him detained.

Judge Hogan would also go on the record to say that al-Madhwani was a “model prisoner” at Guantanamo and explained in court documents, “There is nothing in the record now that he poses any greater threat than those detainees who have already been released.” Other excerpts described the prisoner as “a lot less threatening” than former Gitmo detainees already released, and “at best … the lowest level al-Qaeda member” who should be returned to Yemen. The District Court wrote then that the “basis for continuing to hold him is questionable.”

Although District Court Judge Thomas Hogan found that the prisoner was neither dangerous nor a threat to the United States, he nonetheless insisted that his “hands were tied” and denied al-Madhwani’s petition for a writ of habeas corpus.

On appeal of that decision, the D.C. Circuit Court upheld the lower court’s ruling and that decision was ultimately appealed in a petition for a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court.

In the brief filed by the Obama administration opposing al-Madhwani’s cert petition, the government explicitly and for the first — but certainly not the last time — offers the NDAA as authority for the ongoing detention of “some persons captured” and “detained at Guantanamo Bay.” The historic language in the brief is clear:

In response to the attacks of September 11, 2001, Congress enacted the AUMF [Authorization for the Use of Military Force], which authorizes “the President * * * to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons.” AUMF § 2(a), 115 Stat. 224. The President has ordered the Armed Forces to subdue both the al-Qaida terrorist network and the Taliban regime that harbored it in Afghanistan. Armed conflict with al-Qaida and the Taliban remains ongoing, and in connection with that conflict, some persons captured by the United States and its coalition partners have been detained at Guantanamo Bay. In Section 1021 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 (NDAA), Pub. L. No. 112-81, 125 Stat. 1561 (2011), Congress “affirm[ed]” that the authority granted by the AUMF includes the authority to detain, “under the law of war,” any “person who was part of or substantially supported al-Qaida, the Taliban, or associated forces that are engaged in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners.”

And, further on in the document:

As relevant here, the court of appeals has repeatedly held that an individual may be detained under the AUMF if he was part of al-Qaida at the time of his capture. See, e.g., Al-Adahi v. Obama, 613 F.3d 1102, 1103 (D.C. Cir. 2010) (“The government may * * * hold at Guantanamo and elsewhere those individuals who are ‘part of’ al-Qaida, the Taliban, or associated forces.”), cert. denied, 131 S. Ct. 1001 (2011); accord Al Odah v. United States, 611 F.3d 8, 10 (D.C. Cir. 2010), cert. denied, 131 S. Ct. 1812 (2011); Awad v. Obama, 608 F.3d 1, 11 (D.C. Cir. 2010), cert. denied, 131 S. Ct. 1814 (2011); Al-Bihani v. Obama, 590 F.3d 866, 872 (D.C. Cir. 2010), cert. denied, 131 S. Ct. 1814 (2011); accord NDAA § 1021, 125 Stat. 1561 (“affirm[ing] the authority of the President to * * * detain” any “person who was part of or substantially supported al-Qaida, the Taliban, or associated forces that are engaged in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners”).

The brief and disturbing history of the treatment of habeas corpus petitions in the federal courts was provided in an article published by Jurist:

Federal courts have struggled with habeas corpus rights for Guantanamo detainees. In May, the DC Circuit affirmed a lower court’s decision that Yemeni Guantanamo Bay detainee Musa’ab Omar al-Madhwani is lawfully detained for being part of al Qaeda. In March, the DC Circuit overturned a lower court’s decision granting release to Yemeni Guantanamo detainee Uthman Abdul Rahim Mohammed Uthman. In September 2010, Kuwaiti Guantanamo detainee Fawzi Khalid Abdullah Fahad al Odah petitioned the US Supreme Court to reverse a federal appeals court decision that denied him habeas corpus relief, but the Supreme Court turned down his appeal in April.

Despite being adjudged to be no threat to America’s national security, al-Madhwani, a man who has spent nearly a third of his young life imprisoned without being charged, is likely to spend the rest of his life behind bars because of the deplorable and despotic “authority” of the NDAA.

Americans should take warning from the circumstances of al-Madhwani’s tragic life. Although he was not a citizen of our nation, there is yet another constitutionally-offensive measure on the horizon (the Enemy Expatriation Act) that would allow the federal government to strip a suspect of his American citizenship based on nothing more than a suspicion of “engaging in, or purposefully or materially supporting, hostilities.”

No habeas corpus, no due process, no end of imprisonment, and no citizenship — this is the America of 2012.

Related article:

Washington State Lawmakers Join War on NDAA Indefinite Detention