Bush’s and Obama’s actions since 2001 raise a number of fundamental constitutional questions: Can the President — as Bush tried to do — detain an American citizen indefinitely without trial? Can the President — as Obama claims — kill American citizens without trial? Are Bush’s and Obama’s efforts to detain foreigners indefinitely without trial constitutional? When, if ever, is a “military commission” constitutional? Can U.S. citizens be subject to a military commission? How about foreigners? Do the Bush/Obama military commissions follow the Constitution? And finally, putting aside constitutional principles, are military commissions more effective on a practical level in punishing suspected terrorists? The following are 11 constitutional principles about the trial rights of Americans and foreigners during the “war on terror.”

1. The U.S. Constitution, laws, and treaties signed by the United States guarantee everyone — even foreign terror suspects detained abroad — a trial.

The Bush administration argued in the 2004 Supreme Court case Rasul v. Bush that foreigners detained abroad have no right to a hearing and can be detained indefinitely without any trial whatsoever. The claim goes against the traditional Anglo- American tradition of habeas corpus, which says that no one may be detained without a court hearing justifying the detention. The Bush administration argued that “U.S. courts lack jurisdiction over [habeas corpus] claims.” But the Supreme Court ruled against the Bush administration, 6-3, in the Rasul decision, granting Rasul habeas corpus relief and a trial.

And the Supreme Court was not exercising judicial activism; rather, it was following the clear dictates of the law. The Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution explicitly require a trial and full due process for any “person” the government arrests. The Fifth Amendment reads, “No person shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

The Sixth Amendment defines “due process” as follows: “In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.” In short, while the Fifth and Sixth Amendments do not explicitly require a detainee to be read his rights (i.e., “Miranda rights,” which the Supreme Court invented in the 1960s as an add-on to the Fifth Amendment), all detainees are still “persons” within the meaning of the amendments and are entitled to all the due-process rights of American defendants.

The U.S. government is also a signatory of treaties that guarantee that foreign military fighters be given a trial. Article 43 of the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949), of which the United States is a signatory, bans “the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court, affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.” The U.S. government is bound to respect the Geneva Conventions under Article VI of the Constitution, which guarantees, “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land.”

The rights of foreigners abroad to trial in U.S. courts was most clearly established by the Supreme Court in the 1841 Amistad case. In the Amistad case, a number of Africans who had been kidnapped in Africa and traded to Spanish sailors revolted, taking over the ship La Amistad. They drifted near U.S. waters after the revolt. After some of the Africans had come ashore on Long Island to buy food, American sailors sailed out to the ship and seized it.

In the Amistad case, the Spanish government argued that foreigners captured in international waters (though in U.S. custody) have no rights in U.S. courts. The Spanish Minister to the United States, Chevalier d’Argaiz, argued: “They are morally and legally not in the United States…. They are under the cover of the Spanish flag; and, in that case, they are physically under the protection of a friendly government, but morally and legally out of the territory and jurisdiction of the United States; and, so long as a doubt remains on this subject, no judge can admit the complaint.” The slaves-turned liberators of the Amistad were charged with piracy on the high seas and threatening a massive slave rebellion across the hemisphere, a contemporary equivalent to modern terrorism. The court ruled that the slaves had a right to a trial and that “there is no pretence to say the negroes of the Amistad are ‘pirates’ and ‘robbers;’ as they were kidnapped Africans, who, by the laws of Spain itself were entitled to their freedom,” and set the Africans free.

2. Trials are not given to defendants who “deserve” them; they are administered to everyone in order to sort the guilty from the innocent.

GOP presidential frontrunner Mitt Romney told a South Carolina debate audience back on May 15, 2007 of terror detainees: “I’m glad they’re at Guantanamo. I don’t want them on our soil. I want them on Guantanamo where they don’t get the access to lawyers they get when they’re on our soil. I don’t want them in our prisons. I want them there. Some people have said we ought to close Guantanamo. My view is we ought to double Guantanamo.”

More recently, in an August 11, 2011 presidential debate, Representative Michele Bachmann (R-Minn.) suggested that military tribunals would be better for terror suspects: “Terrorists who commit acts against United States citizens, people who come from foreign countries to do that, do not have any right under our Constitution to Miranda rights.”

Implicit in both statements is that foreign terrorists have not earned the right to a trial. But the question of whether alleged terrorists have not in some sense “earned” or “deserve” a trial is a fundamental misunderstanding of the purpose of trials. Criminal suspects of any kind, foreign or citizen, are not given trials as a gift for something they merit. If they are guilty, they never earned them, and if they are innocent, they should never have been arrested. The purpose of trials is to sort the guilty from the innocent. Indeed, the guilty — like Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, who was tried, found guilty, and put to death — can hardly claim to benefit from a trial. Without a trial, however, the whim of the executive branch becomes law and the innocent get punished along with the guilty.

3. The President’s war powers during wartime do not allow him to abolish trials.

The Fifth and Sixth Amendments limit even the prosecution of war decision-making by the President, as these categorical guarantees contain no exceptions for wartime: As “amendments” to the President’s powers under Article II of the U.S. Constitution, they must amend (which means change, and in this case “limit”) the President’s war powers or the entire purpose of amending the Constitution is pointless.

Even alleged “enemy combatants” who have not been charged with a crime are entitled to due process under the amendments. As the American Bar Association wrote in a memorandum about Bush-era detentions: “While the Sixth Amendment does not technically attach to uncharged ‘enemy combatants,’ there is no dispute that individuals who have been criminally charged do have a Sixth Amendment right to counsel, and it is both paradoxical and unsatisfactory that uncharged U.S. citizen detainees have fewer rights and protections than those who have been charged with serious criminal offenses.”

4. Everyone detained under the law of war is entitled to the presumption of innocence.

The President is bound to follow the law of war, which includes following the Geneva Convention treaties that the U.S. government has signed and ratified. Prisoners of war are “protected persons” under the Geneva Convention and are entitled to special protections and a presumption of innocence. They are not to be forcefully interrogated (beyond name, rank, and serial number). They have a right to retain their personal property, a right to exercise, socialize, and receive

Red Cross/Red Crescent packages, and many other privileges. This is because prisoners of war are deemed not to have committed any moral offenses; i.e., they are not criminals. POWs are simply presumed to be people who are patriotic citizens of the country they were born in (or emigrated to). In short, they are presumed to be innocent of wrongdoing.

The Bush/Obama position is to give terror detainees neither rights as military personnel nor rights as ordinary criminals. The Bush (now Obama) circular argument to detain terror suspects indefinitely can be summed up this way: Terror suspects are under military law, even though they are not military and we will not give them the legal protections of soldiers. We will treat them like criminals, but they are more than just criminals, so they won’t get the protections of criminals either. In short, they won’t have any rights because legally, they’re non-persons.

The U.S. Supreme Court called such a view inconsistent with the U.S. Constitution in the 1866 case Ex Parte Milligan. Milligan was an Indiana resident accused of trying to steal arms and liberate Confederate prisoner-of-war camps during the Civil War (and condemned to death by a military commission). The Milligan court observed that the President cannot take away a man’s rights and deny him both the rights as a soldier and as a criminal. The court concluded: “If he cannot enjoy

the immunities attaching to the character of a [lawful combatant] prisoner of war, how can he be subject to their pains and penalties?”

5. The President’s war powers during a time of conflict do not allow him to create “military commissions” to try terror suspects when real courts are available.

Military tribunals have traditionally been “Article II” courts, set up by the executive branch in cases where there is no functioning civilian or military court system. But nothing in the U.S. Constitution presumes that the President by himself can create a court within the executive branch — effectively making the President judge, jury, and executioner — if Article III (judicial branch) courts are available. To the contrary, under the Constitution only Congress has the power under Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution to create a court: “The Congress shall have Power To … constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme Court.”

Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution also specifies, “The Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury; and such Trial shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any State, the Trial shall be at such Place or Places as the Congress may by Law have directed.” The U.S. Supreme Court also denied in Ex Parte Milligan that a President had the constitutional authority to create a military commission and usurp Congress’ power to create courts at a time when ordinary courts were holding trials: “By the protection of the law human rights are secured; withdraw that protection, and they are at the mercy of wicked rulers, or the clamor of an excited people. If there was law to justify this military trial, it is not our province to interfere; if there was not, it is our duty to declare the nullity of the whole proceedings.” Thus, Milligan was set free by the court.

6. Congress’ power to set up military commissions is limited by the Bill of Rights.

Congress has the power to set up courts under the Constitution’s Article I, Section 8, and there’s nothing in theory that says they can’t set up a military court to try foreign terrorists who have taken up arms in a military capacity against the United States and call it a “military commission.” In recent years, Congress has passed two such laws, the Military Commissions Acts of 2006 and 2009. But this power of Congress is limited by the Fifth and Sixth Amendments, which prohibit these trials from including forced confessions (“be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself) and which guarantee “due process of law” (Fifth Amendment). Again, the Sixth Amendment guarantees that due process consists of a jury trial, a defense attorney with subpoena power, and other procedural protections.

7. Military commissions established under Bush and Obama are neither fair nor constitutional.

President Bush initially set up military commissions solely under executive branch authority. This attempt was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 2006 decision of Hamdan v. Rumsfeld.

Congress responded to this decision by passing the Military Commissions Act (MCA) of 2006, but the Supreme Court struck down the law as unconstitutional. The second-generation Bush military commissions constructed under the MCA were struck down in the 2008 Boumediene v. Bush decision because the law did not conform with the requirements of the Fifth and Sixth Amendments.

After he was elected, President Obama, who opposed military commissions as a candidate, came out for new commissions that were designed to lower the evidentiary bar for obtaining convictions — lower than would be the case in a normal trial. “It’s very hard to piece together a chain of evidence that would meet some of the evidentiary standards that would be required in an Article III court,” Obama stated at a September 10, 2010 press conference announcing the reasoning behind his military commissions.

Though the MCA of 2009 provided more protections for detainees than did the 2006 MCA, not surprisingly, the Obama era military commissions still have substantial constitutional shortcomings, such as admission of secret evidence, admission of hearsay evidence, and the fact that the courts were set up after the supposed offenses had taken place specifically to win convictions of specific prisoners. “What is particularly disappointing is the fact that the government is now openly stating the reason that it is reviving this commissions process is because it is going to be hard to obtain convictions in traditional courts,” Lt. Commander Brian Mizer, a defense attorney at Guantanamo Bay, told the Associated Press after Obama’s decision to revive military commissions. “This would be the first time in our republic that we have created a court system in order to obtain convictions, and that’s more than disappointing.” The Obama military commissions have yet to be appealed.

8. Military commissions have been less successful in convicting and punishing terror suspects.

Recent decisions of military commissions have been regularly overturned by appellate bodies, and the handful of convictions that have not been overturned were not overturned simply because they were not appealed. Salim Hamdan, Osama bin Laden’s driver, was sentenced only to time served and was set free. So he didn’t appeal the verdict. The two remaining military commission guilty verdicts were also not overturned solely because the defendants haven’t challenged their verdicts. Ali Hamza al Bahlul refused to mount a defense during his military commission, and has not appealed his verdict. And Australian David Hicks accepted a plea bargain that allowed him to get out of prison and move back to Australia.

On the other hand, hundreds of terrorists have been convicted in regular criminal courts and are serving long sentences or have received the death penalty. “Let me put this in perspective,” Vice President Joseph Biden told CBS’ Face the Nation February 14, 2010. “There have been three people tried and convicted by the last administration in military courts. Two are walking the street right now. There have been over 300 tried in federal courts by the last administration and by us. They’re all in jail now. None of them are out seeing the light of day.”

9. President Bush detained Americans as well as foreigners without trial.

Many Americans take solace in the belief that detentions without trial were conducted only against foreigners, and not against American citizens, during the Bush administration. But that solace is unfounded. Presidents don’t make such distinctions. U.S. Navy veteran Donald Vance and fellow American Nathan Ertel were detained without trial and subjected to “enhanced interrogation” torture by Bush administration officials for months in 2006.

The torture they endured included denial of food for days at a time, beatings called “walling,” and (alternately) sensory deprivation and sensory overload. The innocent Vance and Ertel were detained because they had become whistleblowers — FBI informants — against the private contractor for which they worked. (People in the company were selling government guns in exchange for liquor.) At least one other American citizen was also detained without trial and tortured, and is now suing the U.S. government anonymously.

Moreover, the Bush administration tried its best to detain two other American citizens without trial indefinitely, taking their cases all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Native-born U.S. citizen Jose Padilla was held without trial for three and a half years. He was only given a military commission trial because the Bush administration was about to lose Padilla v. Rumsfeld in the U.S. Supreme Court, a case in which lawyers for Padilla challenged his detention without trial. Likewise, naturalized U.S. citizen Yaser al-Hamdi was detained without trial until the Bush administration faced losing in the Supreme Court. The Bush administration subsequently cut a plea deal with Hamdi.

10. President Obama doesn’t respect the trial rights of foreigners.

Candidate Obama campaigned on behalf of due process for foreign terror detainees, arguing: The right of habeas corpus allows prisoners to ask a court to determine whether they are being lawfully imprisoned. Recently, this right has been denied to those deemed enemy combatants. Barack Obama strongly supports bipartisan efforts to restore habeas rights. But President Obama issued an executive order March 7, 2011 that allowed for “the executive branch’s continued, discretionary exercise of existing detention authority in individual cases” on an indefinite basis without a trial. Those facing detention without trial include some 50 detainees at the Guantanamo Bay prison that candidate Obama pledged to close, as well as several thousand detainees at bases in Afghanistan (such as at Bagram Air Base near Kabul) and Iraq.

11. President Obama doesn’t respect the trial rights of American citizens and thinks Americans may be killed without trial.

President Obama rode into office criticizing the Bush administration’s practices for handling suspected terrorists, but in many ways has actually become even more autocratic than Bush. President Bush claimed for himself the power to detain terror suspects indefinitely without trial, even Americans. But according to the Washington Post, President Obama now believes he can kill without trial U.S. citizens he suspects are aiding terrorism. Obama’s “assassination list” supposedly contains dozens of U.S. citizens living abroad. Obama administration officials have publicly defended the assassination list.

“To me, terrorists should not be able to hide behind their passports and their citizenship, and that includes U.S. citizens, whether they are overseas or whether they are here in the United States,” Obama’s Deputy National Security Adviser for Homeland Security and Counterterrorism John O. Brennan told the Washington Times in June 2010. Brennan said at that time that “dozens” of American citizens were on Obama’s assassination list. New Mexico native Anwar al-Awlaki is reportedly on the assassination list, but the list itself remains classified. Anwar al-Awlaki is thought to be hiding out from the United States in Yemen, and his chief alleged crime is the making of propaganda videos for al-Qaeda.

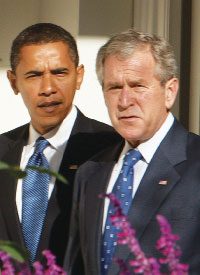

Photo: AP Images

Related article: