Hillary Clinton will not easily be mistaken for Sir Winston Churchill, but our nation’s Secretary of State borrowed a metaphor from old “Winnie” recently when lecturing on the importance of freedom on the Internet. As the former British Prime Minister warned of the communist “iron curtain” descending on Eastern Europe at the beginning of the Cold War, Secretary Clinton has warned of an “information curtain” falling in those nations where governments have used modern technology to suppress and plunder, rather than facilitate, the flow of information among peoples and nations.

The Secretary made her comments in Washington on January 21, nine days after Google had announced its possible withdrawal from China, saying its systems and those of dozens of other companies had been attacked, resulting in the theft of intellectual property and the attempted hacking of g-mail accounts belonging to Chinese human rights activists. China, Tunisia, and Uzbekistan have all stepped up their censorship of the Internet, Clinton said, while noting that 30 bloggers and activists had recently been arrested and jailed in Egypt. The world’s “unprecedented surge in connectivity” is a mixed blessing, she said. “These tools are also being exploited to undermine human progress and political rights.”

Speaking up for human rights is generally commendable, but this might be another example of our government singing the praises of freedom abroad while working to suppress it at home. For on the same day that Secretary Clinton was expounding on the virtues of a free exchange of information and ideas, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down an “information curtain” hung on the American people not by the autocratic rulers of Egypt nor the Politburo of China, but by the Congress of the United States. And the President whom Clinton serves immediately denounced the Court for its action.

Freedom Sounds Good in Theory

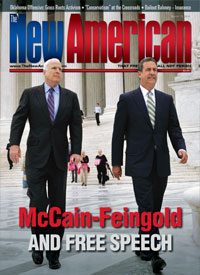

“With its ruling today, the Supreme Court has given a green light to a new stampede of special interest money in our politics,” President Obama said when the ruling was issued. A few days later the President used his State of the Union address to rally congressional and public opinion against the ruling that found provisions of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, better known as McCain-Feingold, violated the freedom of speech guaranteed by the First -Amendment.

“With all due deference to separation of powers, last week the Supreme Court reversed a century of law that I believe will open the floodgates for special interests — including foreign corporations — to spend without limit in our elections,” the President said as the black-robed judges sat in silence before him. “I don’t think American elections should be bankrolled by America’s most powerful interests, or worse, by foreign entities. They should be decided by the American people. And I’d urge Democrats and Republicans to pass a bill that helps to correct some of these problems. The public interest requires nothing less.”

As the President spoke, TV cameras caught Justice Samuel Alito apparently mouthing the words, “Not true.” Some critics of the Court’s decision saw Alito’s visible reaction to the President’s words as a breach of decorum, while at least as many of the Obama’s detractors criticized the President for using the State of the Union gathering as an occasion to lash out at the Court ruling — even with the pro forma expression of “all due deference” to the third branch of government.

The President’s concern about “powerful interests” is highly selective, as we shall see. But the Court’s 5-4 ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission had to do with the freedom of speech of people and organizations that are, in most cases, considerably less powerful than the President, the Congress, or the large media corporations whose editorials and commentaries against the ruling might lead one to believe the Court has sounded the death knell of the Republic.

The Case

The case pitted Citizens United, a non-profit corporation that receives some of its funding from for-profit companies, against a government determined to regulate criticism of itself. The organization of conservative political activists wished to show Hillary: The Movie, on a pay-per-view cable television outlet and run ads for the movie on commercial TV. The video is a documentary about then-Senator and presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, calling into question her fitness for the presidency and urging voters to repudiate her candidacy. Since the movie and the ads for it would be shown within 30 days of a presidential primary, the Federal Election Commission advised the group it would be violating federal law. Citizens United then took its case to the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C., which upheld the FEC. The group’s appeal of that decision eventually reached the Supreme Court.

The majority opinion, written by Justice Kennedy, takes up 183 pages, but its central finding is summed up in one telling paragraph, describing the constitutional flaw in a key section of the statute:

Section 441 b makes it a felony for all corporations — including nonprofit advocacy corporations — either to explicitly advocate the election or defeat of candidates or to broadcast electioneering communications within 30 days of a primary or 60 days of a general election. Thus, the following acts would all be felonies under 441 b: The Sierra Club runs an ad, within the crucial phase of 60 days of a general election, that exhorts the public to disapprove of a Congressman who favors logging in national forests; the National Rifle Association publishes a book urging the public to vote for the challenger because the incumbent U.S. Senator supports a handgun ban; and the American Civil Liberties Union creates a Web site telling the public to vote for a Presidential candidate in light of that candidate’s defense of free speech. These prohibitions are classic examples of censorship.

And they are not mere products of Justice Kennedy’s imagination. The American Civil Liberties Union and the National Rifle Association, in a classic case of politics making “strange bedfellows,” joined plaintiff Citizens United in seeking a Court ruling against the prohibition. Cleta Mitchell, a Washington, D.C., attorney who represented two advocacy groups supporting the challenge, described how the government used McCain-Feingold to come down on the nation’s best-known environmentalist group.

“After the 2004 election, the Sierra Club paid a $28,000 fine to the Federal Election Commission for distributing pamphlets in Florida contrasting the environmental rec-ords of the two presidential and U.S. Senate candidates,” Mitchell wrote in an op-ed piece for the Washington Post. “Because the Sierra Club is a corporation, the FEC charged it with making an illegal corporate expenditure.” That is not an aberration, she noted. “The real victims of the corporate expenditure ban have been nonprofit advocacy organizations across the political spectrum.” Any organization attempting to comply with the law might need a team of lawyers to unravel its complexities.

Free Speech for a Few

“The Federal Election Commission, which administers the law that rations the quantity and regulates the content and timing of political speech, identifies 33 types of political speech and 71 kinds of ‘speakers,’” wrote columnist George Will. “The underlying statute and FEC regulations cover more than 800 pages, and FEC explanations of its decisions have filled more than 1,200 pages.” By contrast, he noted, the First Amendment, which defines the role of Congress with respect to free speech, covers that subject in 10 words: “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech.”

Those 10 words seemed to carry little weight with Members of Congress, including Hillary Clinton, who voted for the “bipartisan” bill in the Senate, or with President George W. Bush, who signed it into law. Nor have they tempered the outrage expressed by President Obama and Democratic lawmakers who are committed to reversing the Court’s decision either by statute or constitutional amendment.

“The bottom line is this,” fumed Senator Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.), “The Supreme Court has just pre-determined the winners of next November’s elections. It won’t be Republicans, it won’t be Democrats, it will be corporate America.” Much of the reporting and commentary in the major news media reflected the widespread doomsaying about the Court’s decision.

The ruling “strikes at the heart of democracy,” according to the New York Times. An authority on political elections was quoted in the Washington Post as saying it “threatens to undermine the integrity of elected institutions across the nation.” Liberal commentator Alan Colmes predicted the decision would lead to a “corporate takeover of America.” Jonathan Alter, in his Newsweek column, called it “the most serious threat to American democracy in a generation.”

The Court’s many twists and turns in its interpretations of constitutionally guaranteed rights over the past several decades have often confounded its critics. One might wonder, for example, why the right to vend pornography in a city’s downtown is deemed constitutionally protected while a voluntary recitation of a nondenominational prayer at a graduation ceremony for a public school violates the First Amendment. The rights of prisoners, including convicted drug dealers and cop killers, are scrupulously protected, while a pre-born infant may be “terminated” as a matter of choice. Twenty years ago, the Court struggled mightily with the question of whether nude dancing in a public lounge was covered by the First Amendment (if nothing else). This year only a bare majority of the Court was willing to assert constitutional protection for political speech. Yet political speech, not nude dancing, is exactly what the First Amendment was written to protect. The issues contested in Citizens United were not, after all, about the banning of Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Perhaps that’s why the American Civil Liberties Union has called itself “a lonely voice in the progressive community” when opposing free-speech restrictions like those in McCain-Feingold. The Greek chorus of “progressives” now issuing ominous warnings of an “activist” Court was singing a remarkably different tune when the Justices were striking down state laws and local ordinances against obscenity, sodomy, and abortion. “Progressive” voices, including those at the ACLU, can be heard celebrating when the Court, in its roving jurisdiction, goes abroad to find, in judicial decisions rendered in far off lands, a rationale for a ruling to overturn a death sentence for a convicted murderer. But faced with the prospect of Citizens United — or the National Rifle Association or a Right to Life Committee — running ads about candidates within the time period specified by McCain-Feingold, the prohibitions in that law look rather appealing to “progressive” minds. And a court that upholds the clear language of the First Amendment against an act of Congress that violates it is accused of “conservative judicial activism.”

In fact, it was a planned independent expenditure ad by a pro-life organization that led to a court finding against an earlier ruling by the FEC. Wisconsin Right to Life Committee, a non-profit corporation, wished to run a TV commercial during the 2004 campaign season that urged voters to call Senators Russ Feingold and Herb Kohl and urge them to support a vote on confirmation of Bush-appointed judges whose nominations had been stalled in the Senate. But since the ad would have run within 60 days of the general election, and Feingold’s name was on the ballot for reelection, the right-to-life group was advised by the FEC that its sponsorship would violate the law. The finding was no doubt pleasing to Senator Feingold, who cosponsored the Senate bill with John McCain.

McCain’s Malfeasance

But the Supreme Court, following a ruling it had issued in Buckley v. Valeo (1976), found the ban an overreach, since the ad in question did not violate the statutory prohibition of expenditures to “expressly advocate” the election or defeat of a candidate. Nonetheless, Senator McCain, whose self-proclaimed penchant for “straight talk” does not include a devotion to free speech, filed an amicus brief on behalf of the Federal Election Commission.

In a 2006 interview with radio talk-show host Don Imus, McCain made it clear that defending the First Amendment was not his priority, his oath to the Constitution notwithstanding. Said the Arizona “maverick”: “I would rather have a clean government than one whose — quote — First Amendment rights are being respected that has become corrupt. If I had my choice, I’d rather have a clean government.” McCain’s dismissive reference to the “quote” First Amendment showed not mere indifference, but outright contempt for a key provision of the Bill of Rights. His guiding light, apparently, is not the Constitution, but his own high-minded sense of moral cleanliness, a sense no doubt sharpened by his experience as one of the “Keating Five” implicated in the Lincoln Savings and Loan Scandal that came to light in 1989. McCain was among the Senators who two years earlier had intervened with chairman of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board on behalf of Charles Keating, an Arizona developer whose California thrift was then under investigation. McCain said he merely wanted to make sure a constituent was being treated fairly.

But Keating was a rather special constituent, who by that time had raised $112,000 for McCain’s three congressional (two House and one Senate) campaigns. McCain had also taken several trips at Keating’s expense, including three to a retreat in the Bahamas. McCain did not report those trips, as required by House rules, until the scandal broke, at which time he reimbursed Keating $13,443 for the flights.

Two years later, federal regulators seized the bank and the ensuing bailout cost taxpayers $2.6 billion, making Lincoln’s banking practices the most costly of the Savings and Loan scandals. In addition, 17,000 Lincoln investors lost $190 million. Keating eventually pleaded guilty to four counts of fraud and served less than five years in prison. A Senate Ethics Committee investigation concluded that McCain was guilty of “poor judgment.”

The Citizens United case presented the Court with a clear case of express advocacy, as the whole point of Hillary: The Movie was to persuade viewers to oppose the Clinton candidacy. Citizens United first inquired of the FEC whether the ads for it could legally be shown within 30 days of a presidential primary. Justice Kennedy noted that the law, while not requiring such prior approval, often makes it a practical necessity. Because a defense against criminal sanctions by the FEC is a difficult and expensive undertaking, organizations wishing to run ads naming candidates often seek an advisory opinion of the FEC first, thus effectively giving that agency the power of prior restraint on speech — exactly the kind of censorship the Founders prohibited with the adoption of the First Amendment.

In its 5-4 ruling, the Court held that independent expenditure ads by corporations or labor unions are protected by the First Amendment. It left in place, however, the ban on direct contributions by corporations or unions to the candidates and their campaigns, something often overlooked in news reports and commentaries on the ruling. Newsweek’s Jonathan Alter, for example, wrote: “If Goldman Sachs wants to pay the entire cost of every congressional campaign in the U.S., the law of the land now allows it.” As Justice Alito might say, “Not true.”

But what if Exxon-Mobil, to cite one possibility, wanted to run negative ads about candidates opposed to offshore drilling? Since the Court’s ruling also left intact the requirement that contributors underwriting independent expenditure ads be publicly identified, that kind of an ad campaign would surely be highlighted in the nation’s newspapers and TV networks. It would likely inspire boycotts of the sponsor’s product by a significant portion of the public. Corporations tend not to welcome such negative publicity.

As for the President’s contention that the ruling “reversed more than a century of law,” most of the campaign finance laws, dating back to 1907, deal with direct contributions to campaigns, not independent expenditure ads not coordinated with a candidate’s campaign. And Obama, a former professor of constitutional law, surely knows that the virtue of following precedent is neither a moral nor legal absolute. “If it were, segregation would be legal, minimum wage laws would be unconstitutional and the government could wiretap ordinary criminal suspects without first obtaining warrants,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts, referring to previous decisions the Court later overturned.

Indeed, the Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision (1954), holding that segregated schools violated the Constitution, also reversed more than a century of law. The Plessy v. Ferguson precedent, holding that “separate but equal” accommodations were constitutionally permissible, was handed down in 1896 and was followed by both the Congress and the courts for nearly six decades. But the Court in that ruling based much of its reasoning on, and quoted heavily from, an 1849 decision of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, upholding segregated schools in the city of Boston.

Cornering the Market on Payouts

Obama’s aversion to powerful “special interests” is also interesting in light of his presidential campaign that ended barely a year and a half ago. As Boston Globe columnist Jeff Jacoby has noted:

In his 2008 White House run, Obama became the first candidate in the modern era to reject public financing, thereby freeing himself to amass a staggering $745 million in campaign contributions. Some of this was “special interest money” — according to the Center for Responsive Politics, Obama’s record-breaking campaign haul included $43 million from lawyers and lobbyists, $19 million from donors connected to the health-care industry, $18 million from investment and commercial banking, $10 million from real estate interests, and $9 million from Hollywood and the television industry.

Perhaps the President “doth protest too much.”

Jacoby also noted that Senator Schumer, who fears “corporate America” will win all of this year’s elections, has received over the past five years contributions from political action committees representing 20 different industries, including insurance, real estate, securities, liquor, and hedge funds. While campaign money collected and dispersed through political action funds is legal, Justice Kennedy noted that not all corporations are able to create PACs.

“PACs are burdensome alternatives; they are expensive to administer and subject to extensive regulations,” Kennedy wrote, noting that every PAC must appoint a treasurer, keep a multitude of records and file frequent reports. “This might explain why fewer than 2,000 of the millions of corporations in this country have PACs,” Kennedy wrote.

As for the President’s claim that the ruling opens the door to influence by foreign corporations, existing law, apart from McCain-Feingold, prohibits foreign corporations from spending money on U.S. elections. The Court opted not to address that issue but appeared to leave the door open for future litigation.

“We need not reach the question of whether the Government has a compelling interest in preventing foreign individuals or associations from influencing our Nation’s political process,” Kennedy wrote. “Section 441 b (of McCain-Feingold) is not limited to corporations or associations that were created in foreign countries or funded primarily by foreign shareholders. Section 441b therefore would be overbroad even if we assumed arguendo that the Government has a compelling interest in limiting foreign influence over our political process.”

Where To?

The whole issue of independent expenditure ads will likely be a matter for litigation if Congress passes legislation to reverse the Supreme Court decision, as the President has urged. Several Members of Congress have already expressed support for that effort and at least three Senators — Democrats John Kerry and Christopher Dodd and Independent Arlen Specter — have voiced support for a constitutional amendment to make the speech restriction enforceable, despite the First Amendment. Dodd’s proposed amendment would authorize Congress to regulate the raising and spending of money for state and federal political campaigns, and to implement and enforce the amendment through “appropriate legislation.”

“Money is not speech,” Dodd said in announcing the move. “Corporations are not people.” But corporations are made up of people who have constitutionally protected rights. Nothing in the Constitution suggests that people lose their right to free speech when joined together in a corporation. And though money is not speech, it is a medium of exchange used to pay for many things, including newsprint and printing presses, TV cameras, microphones, and broadcast towers, as well as advertising. Would Senator Dodd and his like-minded colleagues consider constitutional a law that would limit what news organizations may spend on their publications and broadcasts?

In fact, McCain-Feingold exempted media corporations from the restrictions on corporate spending, which may explain the law’s popularity with much of the “mainstream media.” Media corporations have long held sway over America’s political life, setting the agendas for debates and shaping public thought and attitudes towards issues and candidates. Edward R. Murrow on CBS played a leading role in mobilizing public opinion against Senator Joe McCarthy in the 1950s. Henry Luce, founder of Time-Life, provided much of the glowing publicity that made a media star of John F. Kennedy.

Today, a long series of mergers and acquisitions has given media corporations, their officers, and shareholders a powerful influence over what Americans see, hear, and read about incumbents in high office and the candidates who oppose them. As attorney Mitchell observed: “The Supreme Court has correctly eliminated a constitutionally flawed system that allowed media corporations (e.g., The Washington Post Co.) to freely disseminate their opinions about candidates using corporate treasury funds, while denying that constitutional privilege to Susie’s Flower Shop Inc.”

Susie’s Flower Shop might not be much of a match for the Washington Post or for corporations like AIG or Goldman Sachs, to cite just a couple of the corporations that have benefited from the government’s bailout of large portions of the financial industry. But it is entitled to the same constitutionally protected rights. And it may be that Susie has joined with a great many of her fellow citizens across the land in corporations representing environmentalists or developers, gun owners or gun banners, pro-lifers or champions of abortion “rights.” These citizens have, by incorporating, pooled their resources and are now free to advertise their views of candidates and issues at times and places of their own choosing. But incumbent officeholders, who have most to fear from citizen evaluations of their records and conduct, and the “mainstream” media, which like to dominate public discussions of candidates and issues, have a vested interest in keeping such people and organizations out of the debate.

Perhaps Susie should move her flower shop to China, where our Secretary of State is concerned about the rights of people behind the “information curtain,” even as she, her President, and many of her former Senate colleagues appear oblivious to the free-speech rights of people here in the United States.