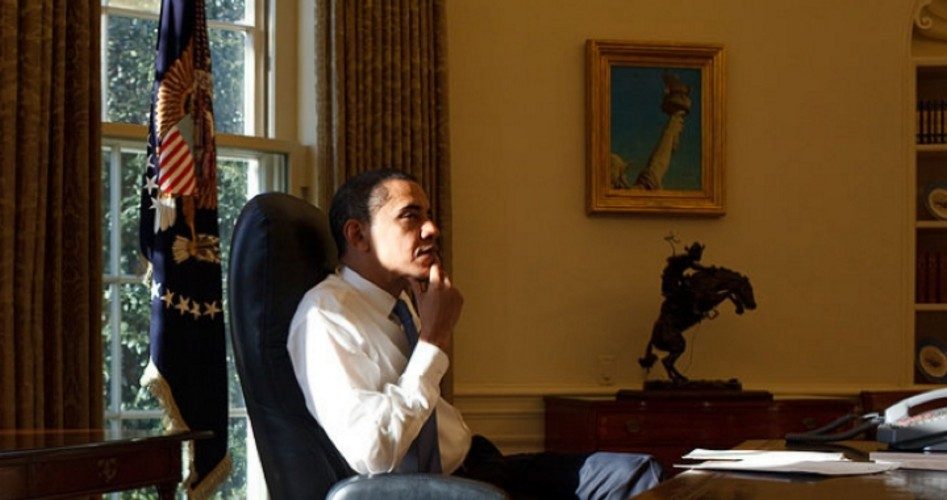

President Obama continues his assault on the “irrelevant” Constitution by bypassing Congress and violating current law in the process of making executive branch appointments. But the Supreme Court will be hearing a case in November on this very issue.

Article II, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution provides for the participation of the Senate in the appointment process of “officers of the United States” nominated by the president. Specifically, the Senate is to give its “advice and consent.”

This process has proven too slow in practice, so Congress has enacted legislation permitting the president to appoint temporary officeholders (typically limited to a maximum period of service of 210 days) without seeking the advice and consent of the Senate.

Given that Congress appreciates that presidents endowed with such exceptional power would be prone to abuse it, another limitation has been added to the maximum length of the temporary service.

According to the latest iteration of the Federal Vacancies Reform Act (FVRA), “a person may not serve as an acting officer” and then be subsequently appointed to serve in that capacity permanently (with an exception applying to “longtime first assistants”).

As has become his habit, however, President Obama ignored this provision of the law and in 2011 he nominated Lafe Solomon to serve as general counsel to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) while he was already serving temporarily in that same post. This is an obvious violation of the the FVRA.

Later, while serving as acting general counsel and after his nomination to become the permanent general counsel, Solomon initiated an action against SW General, an ambulance company.

Shrewdly, SW General objected to the proceeding, citing the illegal dual status of Solomon as acting and permanent general counsel at NLRB, the agency bringing the action against SW General.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled in favor of SW General, but the NLRB has appealed the decision to the Supreme Court.

The D.C. court’s holding is solid, relying on the clear intent of the Framers of the Constitution in checking executive power through the participation of the legislative branch in the appointment process.

In The Federalist, No. 76, Alexander Hamilton explains that the Constitution “requires” the cooperation of the Senate in appointments in order to “check” the president and “to prevent the appointment of unfit characters”; and that “the necessity of its [the Senate’s] co-operation, in the business of appointments, will be a considerable and salutary restraint upon the conduct of that magistrate [the president].”

Addressing the issues underlying the current constitutional crisis specifically, in The Federalist, No. 68, Hamilton discussed the Recess Appointment Clause:

The ordinary power of appointment is confided to the president and senate jointly, and can therefore only be exercised during the session of the senate; but, as it would have been improper to oblige this body to be continually in session for the appointment of officers; and as vacancies might happen in their recess, which it might be necessary for the public service to fill without delay, the succeeding clause is evidently intended to authorize the president, singly, to make temporary appointments “during the recess of the senate, by granting commissions which should expire at the end of their next session.

What, then, was the role the Senate was designed to play in the nomination and appointment process? Alexander Hamilton wrote in The Federalist:

To what purpose then require the co-operation of the senate? I answer, that the necessity of their concurrence would have a powerful, though in general, a silent operation. It would be an excellent check upon a spirit of favoritism in the president, and would tend greatly to prevent the appointment of unfit characters from state prejudice, from family connexion, from personal attachment, or from a view to popularity. In addition to this, it would be an efficacious source of stability in the administration.

It would seem, then, that not even President Obama’s immeasurable regard for his own moral, legal, and intellectual superiority can justify his disregard for the clear blackletter of the FVRA and of Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution.

A summary of the case and the circumstances involved published by the Cato Institute support the Senate’s role in the appointment process:

When the Constitution sets such a default equilibrium between two branches of government, the Supreme Court has recognized that the burden must always be on those who would alter that equilibrium. Absent a clear statement of Congress, the constitutional presumption is that both the president and the Senate must assent to the appointment of every high-ranking official, whether serving permanently or for a limited tenure. Giving the benefit of the doubt to an unauthorized appointment like that of Lafe Solomon would turn this presumption on its head.

Cato has filed an amicus brief in the Solomon case and is hopeful that the Supreme Court will “reject [President Obama’s] overreach” in this case as it did in 2014 in another case involving the NLRB.

In 2014, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld a federal appeals court ruling that President Obama’s 2012 recess appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) were unconstitutional.

Specifically, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit held that the recess appointments violated the Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution, the so-called Appointments Clause.

In 2012, President Obama used recess appointments to fill three seats on the National Labor Relations Board, arguing that the appointments were made in complete compliance with his Article II powers.

The majority of the D.C. Appeals Court disagreed, writing:

The [NLRB] conceded at oral argument that the appointments at issue were not made during the intersession recess: the President made his three appointments to the Board on January 4, 2012, after Congress began a new session on January 3 and while that new session continued. Considering the text, history, and structure of the Constitution, these appointments were invalid from their inception. Because the Board lacked a quorum of three members when it issued its decision in this case on February 8, 2012, its decision must be vacated. [Citations contained in the opinion have been omitted in this article.]

On November 6, the Supreme Court will hear the Solomon case and will have an opportunity to once again force President Obama to submit to the statutory and constitutional limits on his appointment authority.