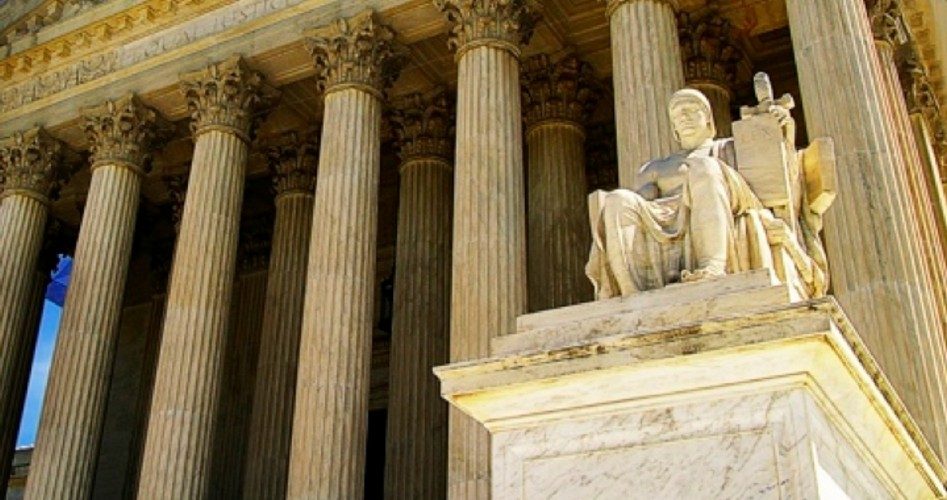

The Supreme Court justices will be very busy during June, prior to breaking for summer vacation. Remarkably, there are 25 pending cases, several of which deal directly with issues of substantial constitutional concern, including recess appointments and the separation of powers doctrine.

First up is a case challenging President Obama’s abuse of executive appointment power.

One of the central questions facing the justices in the case of Noel Canning v. National Relations Labor Board (NLRB) is when is a recess not a recess.

President Obama appointed members to the NLRB without the consent of the Senate, claiming the Senate was in recess, though the Senate viewed itself as being in session. When the Senate actually is in recess, the Constitution allows the president to appoint officials without consent of the Senate.

The president’s going to have a long row to hoe to convince a majority of the justices that he didn’t violate the limits of that provision, however, when he chose to place his own will above the Senate’s claim that it was indeed in session.

In January 2013, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit held that the recess appointments violated Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution, the so-called Appointments Clause.

This clause states that the president shall “nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law.”

The plain language of the clause in question authorizes the president to make appointments when the Senate is in recess. If such is the case, then the president is within the sphere of his constitutionally enumerated powers to fill a vacancy that will be valid until the end of the next congressional session.

Article II also makes it clear that the Senate must already be in recess in order for an appointment made in its absence to be valid. Here’s where President Obama’s actions seem to part ways with the Constitution.

Not surprisingly, though, Attorney General Eric Holder defended the president’s questionable appointments. In a memo dated January 6, 2012, Department of Justice officials cited various scholarly and bureaucratic interpretations of the Recess Appointment Clause of Article II in order to buttress their opinion:

This Office has consistently advised that “a recess during a session of the Senate, at least if it is sufficient length, can be a ‘Recess’ within the meaning of the Recess Appointments Clause” during which the President may exercise his power to fill vacant offices.

Although the Senate will have held pro forma sessions regularly from January 3 through January 23, in our judgment, those sessions do not interrupt the intrasession recess in a manner that would preclude the President from determining that the Senate remains unavailable throughout to “‘receive communications from the President or participate as a body in making appointments.’”

Thus, the President has the authority under the Recess Appointments Clause to make appointments during this period.

The Founders felt otherwise. In The Federalist, No. 76, Alexander Hamilton explains that the Constitution “requires” the cooperation of the Senate in appointments in order to “check” the president and “to prevent the appointment of unfit characters”; and that “the necessity of its [the Senate’s] co-operation, in the business of appointments, will be a considerable and salutary restraint upon the conduct of that magistrate [the president].”

Addressing the matters underlying the key issues facing the Supreme Court in the Canning case, Hamilton, in The Federalist, 68, wrote specifically about the Recess Appointments Clause:

The ordinary power of appointment is confided to the president and senate jointly, and can therefore only be exercised during the session of the senate; but, as it would have been improper to oblige this body to be continually in session for the appointment of officers; and as vacancies might happen in their recess, which it might be necessary for the public service to fill without delay, the succeeding clause is evidently intended to authorize the president, singly, to make temporary appointments “during the recess of the senate,” by granting commissions which should expire at the end of their next session.

What, then, was the role the Senate was designed to play in the nomination and appointment process? Again, Alexander Hamilton explains the relationship in The Federalist:

To what purpose then require the co-operation of the senate? I answer, that the necessity of their concurrence would have a powerful, though in general, a silent operation. It would be an excellent check upon a spirit of favoritism in the president, and would tend greatly to prevent the appointment of unfit characters from state prejudice, from family connexion, from personal attachment, or from a view to popularity. In addition to this, it would be an efficacious source of stability in the administration.

Next up is a case with immeasurable implications for the future of the sovereignty of the United States, as the president pushes for ratification of a couple of key power grabs masquerading as “treaties”: the United Nations’ Arms Trade Treaty and the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

At issue in the case of Bond v. United States is whether the federal government exceeded its constitutional authority in the prosecution of a woman convicted of attempting to poison an acquaintance.

Carol Bond was incensed that her former friend had an affair with her husband. She was so angry, in fact, that she bought chemicals and tried several times to poison the lady, now pregnant with Bond’s husband’s baby.

In order to poison the lady, Bond put chemicals on the handle of the lady’s front door, car, and mailbox. After learning of the attacks, the lady informed the police who apparently failed to act, so she told the mailman. The mailman informed superiors who called in federal investigators, under the belief that mailboxes are the property of the federal government. The New American’s Bob Adelmann tells the rest of the story:

After surveillance revealed that Bond had used government property in her attempts to poison her former friend, the investigators charged Bond under a statute Congress passed to implement the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), which the Senate ratified in 1997. She was convicted and sent to jail for six years, followed by another five years’ probation, and fined $12,000.

Bond’s attorney argues that in passing a law to implement the CWC, the federal government “exceeded the federal government’s enumerated powers, violated bedrock federalism principles guaranteed under the 10th Amendment and impermissibly criminalized conduct that lacked any nexus to a legitimate federal interest.”

Adelmann also points to the material constitutional consideration in the Bond case:

What’s at stake is the core of federalism: the separation of powers doctrine embedded from birth in the Constitution. As Bond’s petition, drawn by Clement, says, “The absence of a national police power is a critical element of the Constitution’s liberty-preserving federalism.”

When it comes to treaties — or any act passed by Congress for that matter — the analysis must begin by looking within the four corners of the Constitution.

It only makes sense that the federal government cannot enter into a treaty that would contravene the Constitution. If I tell my teenage son that he can drive my car to the movies, does that give him permission to drive it into a lake?

To put a finer point on it, Article VI of the Constitution says:

This Constitution, and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.

That means that in order to have any lawful effect, the object of any treaty signed by the president and ratified by the Senate must lie within their constitutional authority (“the authority of the United States”).

Thomas Jefferson echoed that point specifically as it pertains to the topic of treaties. He wrote, “In giving to the President and Senate a power to make treaties, the Constitution meant only to authorize them to carry into effect, by way of treaty, any powers they might constitutionally exercise.”

At another time, Jefferson reiterated this principle of constitutional construction, saying, “Surely the President and Senate cannot do by treaty what the whole government is interdicted from doing in any way.”

In a letter to his colleague, collaborator, and friend, James Madison, Jefferson agreed that “the objects on which the President and Senate may exclusively act by treaty are much reduced” by application of the principle that a treaty cannot contradict the Constitution and yet still enjoy the approval of that document.

The next article in this series will highlight a couple of other cases expected to be decided by the Supreme Court in June. That article will also examine whether the Founders intended the Supreme Court to be the ultimate arbiter of constitutionality. Spoiler alert: They didn’t!

Joe A. Wolverton, II, J.D. is a correspondent for The New American and travels nationwide speaking on nullification, the Second Amendment, the surveillance state, and other constitutional issues. Follow him on Twitter @TNAJoeWolverton and he can be reached at [email protected].