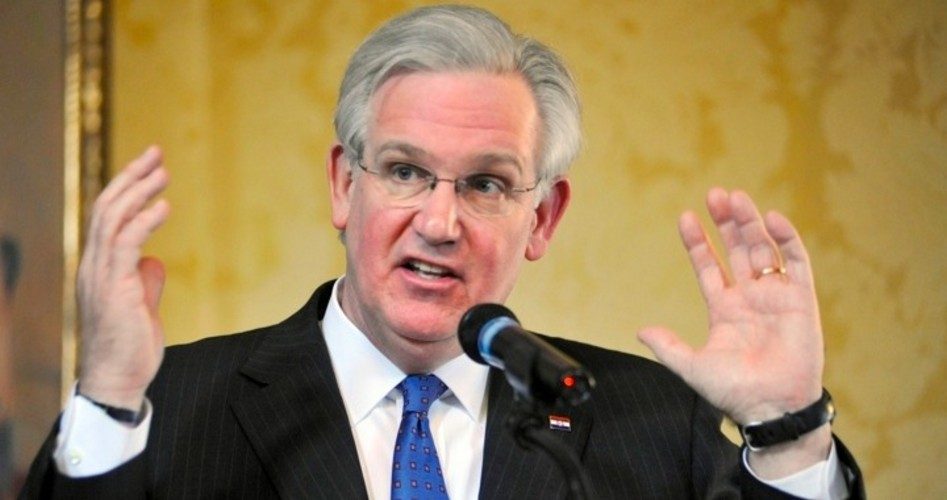

Governor Jay Nixon (shown) declared his independence from the Missouri state legislature on July 5 by vetoing a bill passed overwhelmingly by that body.

With the issuing of a terse, constitutionally confused letter, Nixon notified the secretary of state of Missouri that he refused his assent to HB 436 and why he made that decision. HB 436 was titled the “Second Amendment Preservation Act” and would have denied to the federal government the authority to enact any statutes, rules, regulations, or executive orders “which restrict or prohibit the manufacture, ownership, and use of firearms, firearm accessories, or ammunition exclusively within the borders of Missouri.”

Now, one supposes, the federal government is free to impose its unconstitutional control of the God-given right to keep and bear arms within the formerly sovereign borders of the Show Me State.

In fairness, though, Nixon cannot be blamed too harshly for vetoing the bill. The constitution of the state of Missouri separates the state government into three distinct branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. In similar fashion to the federal Constitution, the Missouri constitution balances the powers of government, checking one against the others so that no one branch “shall exercise any power properly belonging to either of the others.”

In light of that fact of constitutional construction of the Missouri charter, Nixon was within his rights to reject the Second Amendment Preservation Act, regardless of the level of legislative support the measure enjoyed.

Going forward, the true test of the state legislature’s commitment to the principles set forth in HB 436 will be whether it can muster the will to exercise another article of the state constitution: Article III, Section 32.

That provision of the state constitution provides that if two-thirds of both houses of the general assembly vote to pass the bill, “the objections of the governor thereto notwithstanding,” then the bill becomes law, regardless of the veto.

Both the state Senate and the state House of Representatives passed the Second Amendment Preservation Act by majorities greater than the two-thirds required to override the governor’s veto.

For his part, in his veto notification letter, Governor Nixon lists his objections under two headings: Supremacy Clause violation and First Amendment free speech clause violations. The explanation given under the second section is such a stretch as to obviate any need to deconstruct. As to the first, it demonstrates a common constitutional misunderstanding and thus merits correction.

The Supremacy Clause (as some wrongly call it) of Article VI does not declare that federal laws are the supreme law of the land without qualification. What it says is that the Constitution “and laws of the United States made in pursuance thereof” are the supreme law of the land.

Read that clause again: “In pursuance thereof,” not in violation thereof. If an act of Congress is not permissible under any enumerated power given to it in the Constitution, it was not made in pursuance of the Constitution and therefore not only is not the supreme law of the land, it is not the law at all.

Constitutionally speaking, then, whenever the federal government passes any measure not provided for in the limited roster of its enumerated powers, those acts are not awarded any sort of supremacy. Instead, they are “merely acts of usurpation” and do not qualify as the supreme law of the land. In fact, acts of Congress are the supreme law of the land only if they are made in pursuance of its constitutional powers, not in defiance thereof.

Alexander Hamilton put an even finer point on the issue when he wrote in The Federalist, No. 78, “There is no position which depends on clearer principles, than that every act of a delegated authority contrary to the tenor of the commission under which it is exercised, is void. No legislative act, therefore, contrary to the constitution, can be valid.”

Once more legislators, governors, citizens, and law professors realize this fact, they will more readily and fearlessly accept that the states are uniquely situated to perform the function described by Madison above and reiterated in a speech to Congress delivered by him in 1789. “The state legislatures will jealously and closely watch the operation of this government, and be able to resist with more effect every assumption of power than any other power on earth can do; and the greatest opponents to a federal government admit the state legislatures to be sure guardians of the people’s liberty,” Madison declared.

To the credit of the authors of HB 436, the bill opens with a brief recitation of the history of the creation of the federal government, a recounting that resounds with a firm grasp on the proper, constitutional relationship between state and federal governments, as well as the legal basis for nullification:

Acting through the United States Constitution, the people of the several states created the federal government to be their agent in the exercise of a few defined powers, while reserving to the state governments the power to legislate on matters which concern the lives, liberties, and properties of citizens in the ordinary course of affairs;

The limitation of the federal government’s power is affirmed under the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which defines the total scope of federal power as being that which has been delegated by the people of the several states to the federal government, and all power not delegated to the federal government in the Constitution of the United States is reserved to the states respectively, or to the people themselves;

Whenever the federal government assumes powers that the people did not grant it in the Constitution, its acts are unauthoritative, void, and of no force;

The several states of the United States of America are not united on the principle of unlimited submission to their federal government. If the government created by the compact among the states were the exclusive or final judge of the extent of the powers granted to it by the Constitution, the federal government’s discretion, and not the Constitution, would be the measure of those powers.

Something a vast majority (again, a veto-proof majority) of Missouri lawmakers understands is that the federal government is the creature of the states, not their creator. The states provisionally delegated a portion of their sovereignty to the federal government and they specifically enumerated that authority in the Constitution.

Federal exercise of power, as understood by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, is legitimate only if those powers were granted to the federal government by the people and listed specifically in the Constitution.

In the Virginia Resolution, Madison described any attempt by the federal government to act outside the boundaries of its constitutional powers as a “dangerous exercise,” and reminded state legislatures that they were “duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil.”

Considering, then, that the Second Amendment to the Constitution explicitly forbids the federal government from infringing on the right of citizens to keep and bear arms (“shall not infringe …”) any movement by Congress or the White House in that direction certainly passes Madisonian muster for state nullification.

The only question remaining, it seems, with regard to the future of the right to keep and bear arms in Missouri is whether the people’s representatives in the state legislature will assert their constitutional authority and pass the bill a second time, thus making it the law, despite the governor’s misunderstanding of the Supremacy Clause and states’ rights to rule.

On that point, a story published by CNN reports:

State House Speaker Tim Jones, a Republican, reacted with shock to the veto and vowed to override it. The governor “generally has been an ardent supporter of the Second Amendment. I think he made a political, calculated move to veto House Bill 436,” Jones said in an interview with St. Louis Public Radio. “I really don’t know what got to him other than special interest groups on the left.”

Missourians will now be watching to see whether this “shock” will be enough to prod the legislature to do the right thing and protect the Second Amendment in the state of Missouri.

Photo of Gov. Jay Nixon: AP Images

Joe A. Wolverton, II, J.D. is a correspondent for The New American and travels frequently nationwide speaking on topics of nullification, the NDAA, and the surveillance state. He can be reached at [email protected]