Only days before the U.S. Supreme Court is expected to issue rulings on two controversial cases involving same-sex marriage, Justice Antonin Scalia told a state bar association that judges are not fit arbiters of moral standards, the Charlotte Observer reported. Speaking in Asheville Friday at an annual meeting of the North Carolina Bar Association, the veteran jurist argued against what he described as a growing belief in the role of the “judge moralist” in deciding a wide array of moral and ethical questions, including abortion, doctor-assisted suicide, the death penalty, and same-sex marriage. Judges are not experts on moral issues and many of the questions brought to the court have no “scientifically demonstrable right answer,” Scalia said in a speech titled, “Mullahs of the West: Judges as Moral Arbiters.”

The Supreme Court is expected this week to announce decisions on two much-watched and highly publicized cases concerning same-sex marriage. One is a challenge to the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) that defines marriage in federal law as a union between one man and one woman. The other is a suit alleging that California’s Proposition 8, adopted by referendum in 2008, violates the constitutional guarantee of “equal protection of the laws” by denying marriage to same-sex couples. While not addressing either case in his remarks to the bar association, Scalia has, both in prior speeches and in his court opinions, often expressed a willingness to leave moral issues with the states and to prevailing community standards, rather than having them decided by the national judiciary. Known for his belief in interpreting provisions of the Constitution according to the “original intent” of its authors, Scalia acknowledged during the question-and-answer segment of his presentation that many judges and legal scholars favor interpretations of a ‘living Constitution” that embodies “evolving standards of decency.” The courts are often confronted with new issues and arguments, he conceded, but he said they should rule according to constitutional principles as understood and ratified in the adoption of the original Constitution and subsequent amendments. Most moral issues, he said, are not new, though popular opinion concerning them may change. He questioned “the propriety, the sanity” of having such “value-laden” decisions “made for the entire society by unelected judges,” warning: “We have become addicted to abstract moralizing.”

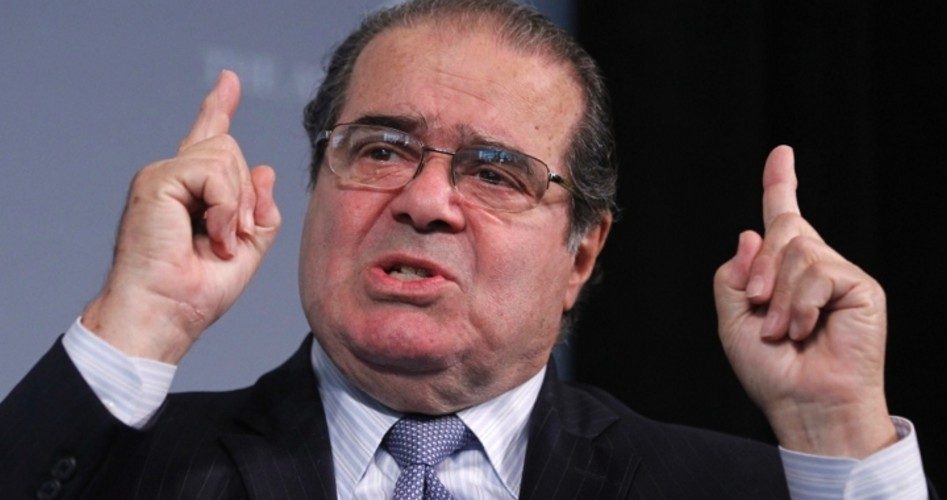

Scalia, 77, is the longest serving and, arguably, the most conservative justice among current members of the Supreme Court. He was appointed by President Ronald Reagan and confirmed by the U.S. Senate in 1986. He is noted for frequently issuing sharply worded dissents when a majority of his colleagues embrace a new and more expansive interpretation of a constitutional provision than his jurisprudence of original intent would allow. In dissenting from a 2003 ruling that overturned a Texas anti-sodomy law, Scalia wrote that people are entitled to protect themselves and their communities form “a lifestyle that they believe to be immoral and destructive.” He is often skeptical of new claims to rights nowhere mentioned in the Constitution, and has been openly scornful of a claim made by Justice Anthony Kennedy in defense of the Roe v. Wade ruling that abortion is a constitutional right. “At the heart of liberty,” Kennedy wrote in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, “is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” Scalia has derided that as the “famed sweet-mystery-of-life passage.”

“Nobody ever thought the Constitution prevented restrictions on abortion,” Scalia said in a speech to the American Enterprise Institute last October. “Homosexual sodomy? Come on. For 200 years it was criminal in every state.” In March, during oral arguments on same-sex marriage, Scalia raised the question: “When did it become unconstitutional to exclude homosexual couples from marriage?”

While the jurist’s 35-minute speech in Asheville elicited applause and laughter, not all the lawyers present agreed with his “originalist” approach to interpreting the Constitution. Raleigh attorney John Sarrat asked Scalia for his view of the unanimous Supreme Court decision ruling segregated public schools unconstitutional in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling. Scalia said he would have supported that decision, but said the states would have eventually removed the racial barriers even without the court mandate. A good result does not necessarily make good law, he said. Sarrat disagreed.

“I tend to be outcome-based,” he told the Observer. “And if the outcome is equality for all people, then I’m for the courts moving in that direction, before the people are ready.”