During my student days at a UCLA economics department faculty/graduate student coffee hour in the 1960s, I was chatting with Professor Armen Alchian, probably the greatest microeconomic theory economist of the 20th century. I was trying to impress Alchian with my knowledge of statistical type I and type II errors. I explained that unlike my wife, who assumed that everyone was her friend until they prove differently, my assumption was everyone was an enemy until they proved otherwise. The result: My wife’s vision maximized the number of her friends but maximized her chances of betrayal. My vision minimized my chances of betrayal at a cost of minimizing the number of my friends.

Alchian, donning a mischievous smile asked, “Williams, have you considered a third alternative, namely, that people don’t give a damn about you one way or another?” Initially, I felt a bit insulted, and our conversation didn’t go much further, but that was typical of Alchian — saying something profound, perhaps controversial, without much comment and letting you think it out.

Years later, I gave Alchian’s third alternative considerable thought and concluded that he was right. The most reliable assumption, in terms of the conduct of one’s life, is to assume that people don’t care about you one way or another. It’s an error to generalize that people are friends or enemies, or that people are out to either help you or hurt you. To put it more crudely, as Alchian did, people don’t give a damn about you one way or another.

Let’s apply this argument to issues of race. Listening to some people, one might think that white people are engaged in an ongoing secret conspiracy to undermine the achievement and well-being of black people. Their evidence is low black academic achievement and high rates of black poverty, unemployment and incarceration. For some, racism is the root cause of most black problems including the unprecedentedly high black illegitimacy rate and family breakdown.

Are white people obsessed with and engaged in a conspiracy against black people? Here’s an experiment. Walk up to the average white person and ask, “How many minutes today have you been thinking about black people?” If the person isn’t a Klansman or a gushing do-gooder liberal, his answer would probably be zero minutes. If you asked him whether he’s a part of a conspiracy to undermine the achievement and well-being of black people, he’d probably look at you as if you were crazy. By the same token, if a person asked me: “Williams, how many minutes today have you been thinking about white people?” My answer would probably be, “Not even a nanosecond.” Because people don’t care about you one way or another doesn’t mean they wish you good will, ill will or no will. They just don’t give a damn.

What are the implications of the people-don’t-care vision of how the world works? A major implication is that one’s destiny, for the most part, is in one’s hands. How you make it in this world depends more on what you do as opposed to whether people like or dislike you. Black politicians, civil rights leaders and white liberals have peddled victimhood to black people, teaching them that racism is pervasive and no amount of individual effort can overcome racist barriers. Peddling victimhood is not new. Booker T. Washington said: “There is a class of colored people who make a business of keeping the troubles, the wrongs and the hardships of the Negro race before the public. Some of these people do not want the Negro to lose his grievances, because they do not want to lose their jobs.” In an 1865 speech to the Anti-Slavery Society in Boston, abolitionist Frederick Douglass said that people ask: “‘What shall we do with the Negro?’ I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us!” Or as Patrick Moynihan urged a century later in a 1970 memo to President Richard Nixon, “The time may have come when the issue of race could benefit from a period of ‘benign neglect.’”

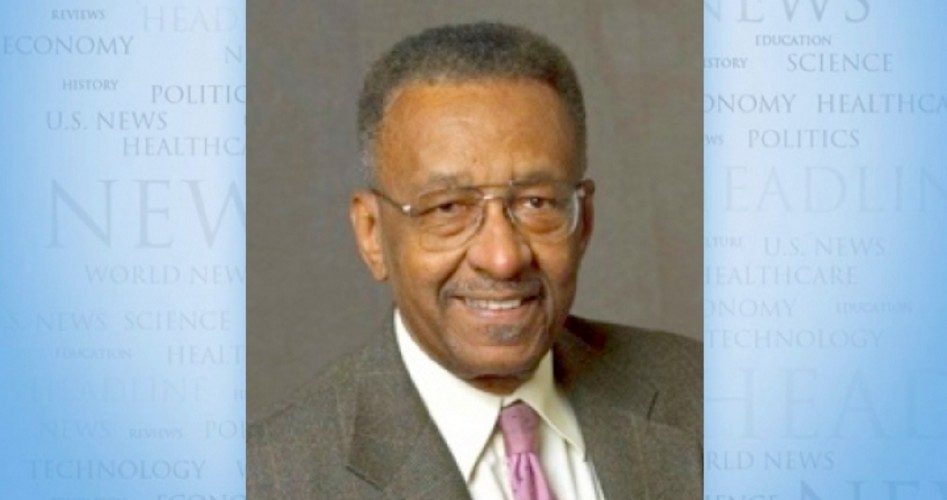

Walter E. Williams is a professor of economics at George Mason University. To find out more about Walter E. Williams and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate webpage at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2019 CREATORS.COM