The case currently before the U.S. Supreme Court, involving racial double standards in admissions to the University of Texas at Austin, has an Alice-in-Wonderland quality that has been all too common in other Supreme Court cases involving affirmative action in academia, going all the way back to 1978.

Plain hard facts dissolve into rhetorical mysticism in these cases, where evasions of reality have been the norm.

One inconvenient reality is that racial double standards by government institutions are contrary to the “equal protection of the laws” prescribed by the 14th Amendment to the constitution. Therefore racial double standards must be called something else — whether “holistic” admissions criteria or a quest for the many magical benefits of “diversity” that are endlessly asserted but never demonstrated.

Such mental gymnastics are not peculiar to the Supreme Court of the United States. I encountered the same evasive language in other countries with group preference programs, during the years when I was doing research for my book Affirmative Action Around the World. This was one of the sadder examples of the brotherhood of man.

When the courts in India tried to rein in some of the more extreme group quota policies in academia, that only inspired more ingenuity by university officials, who came up with more subjective admissions criteria.

At one medical school in India’s state of Tamil Nadu, those criteria included extracurricular activities, “aptitude” and “general abilities” — as determined by interviews that lasted approximately three minutes per applicant. The ratings on these vague, wholly subjective criteria could then be used to offset some students’ academic deficiencies, and thus preserve group quotas de facto.

Another common feature of group preference policies in various countries in different parts of the world is the illusion that these preferences can be confined to some transitional time period, after which the preferences will fade away.

Even in countries where a time frame was specified at the outset — as in Pakistan, India and Malaysia, for example — the preferences have persisted for generations past those cutoff dates. Yet the Supreme Court of the United States has repeatedly indulged in the same illusion of transitional group preferences.

Such preferences have not only extended in time, they have spread to more activities and more groups. In India, it was declared that preferential treatment in the academic admissions process would end there, and not extend to treatment of the preferred groups once they were students in the university.

Yet preferential grading of students admitted with lower qualifications became so widespread in India that these grades acquired the name “grace marks.” In Malaysia, committees were authorized to adjust grades to enable the preferred Malay students to be — or to seem — more comparable to the non-preferred Chinese students.

In the days of the Soviet Union, professors were pressured to give higher grades to Central Asian students. In New Zealand, softer courses in Maori studies achieved similar results. In the United States, easy ethnic studies courses serve the same purpose. When I taught at Brandeis University, many years ago, an academic administrator confided to me that one of his chores was phoning professors to see if they would “reconsider” failing grades given to minority students.

Often the rationale for group preferences is to help the less fortunate. But, in countries where hard evidence is available, it is often the more fortunate members of less fortunate groups who get the bulk of the benefits. These beneficiaries can even be more fortunate than most of the people in the country at large.

India’s constitution, like the American constitution, has an amendment prescribing equal treatment. But in India that amendment also spells out exceptions for particular groups. In the United States, the Supreme Court has taken on the role of creating exceptions to the 14th Amendment.

Many lofty verbal evasions are necessary, in order to keep the American people from catching on to what they are really doing when they claim to be merely applying the laws and the constitution.

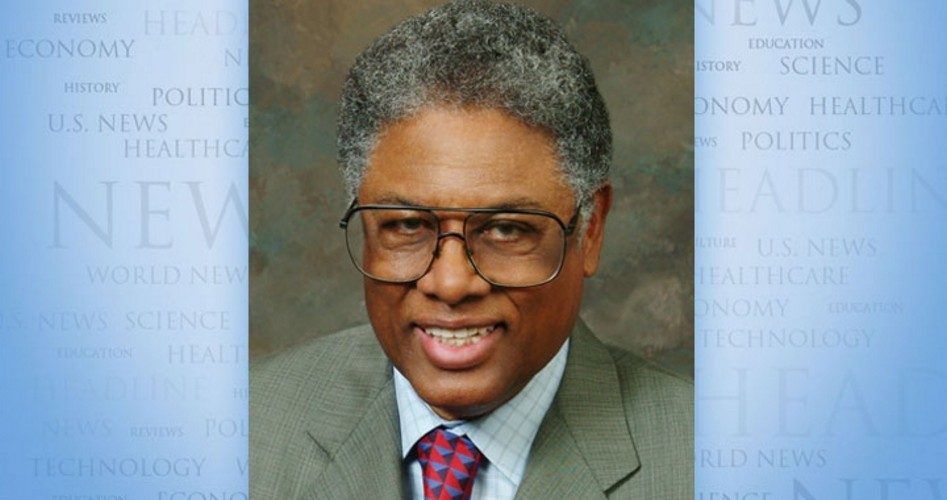

Thomas Sowell is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305. His website is www.tsowell.com. To find out more about Thomas Sowell and read features by other Creators Syndicate columnists and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

COPYRIGHT 2015 CREATORS.COM