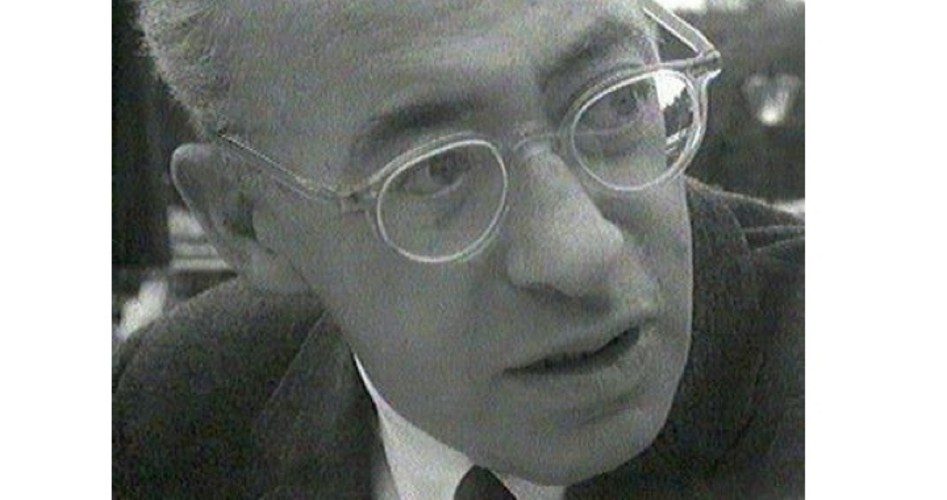

For anyone who bothered to properly vet Hillary Clinton during her campaign for New York Senate and for the Democratic presidential nomination, Clinton’s allegiance to radical Chicago community organizer Saul Alinsky (shown) is not new information. The recent publication of Clinton’s correspondence with the left-wing organizer, however, may finally propel that relationship into national attention as it makes a strong statement about her true ideology.

The late Alinsky was a self-proclaimed radical who advocated socialism as a means to improve the disparity between the “haves,” as he dubbed the middle class and wealthy, and the “have-nots,” referring to the poor. He was a supporter of the philosophy that the ends justify the means, and applied that philosophy to his ideas for community organizing.

Alinsky is perhaps best known for his influential book Rules for Radicals, a virtual manifesto for organizers on the Left. A quick perusal of this work provides significant insight into the type of man Alinsky was, the ideas he advocated, and ultimately just how influential he has been on the Obama administration in particular.

In his dedication at the beginning of that book, Alinsky pays homage to one particular idol, “Lest we forget, at least an over the shoulder acknowledgement to the very first radical: from all of our legends, mythology, and history … the first radical known to man who rebelled against the establishment and did it so effectively that he at least won his own kingdom.” That radical was Lucifer.

Alinsky was a proponent of fanning the flames of hostility. He wrote in Rules for Radicals that the organizer must “rub raw the resentments of the people of the community; fan the latent hostilities of many of the people to the point of overt expression.”

He must make the people “feel so frustrated, so defeated, so lost, so futureless in the prevailing system that they are willing to let go of the past and chance the future.”

In the same book, Alinsky contends that a true community organizer “does not have a fixed truth; truth to him is relative and changing; everything to him is relative and changing.” He is a political relativist. (Some say this may be where Obama’s former regulatory czar Cass Sunstein’s philosophy on conspiracy theories is grounded.) Critics note that it sounds like a page right out of George Orwell’s 1984 — the idea that fixed truths are a danger and must be eliminated.

Quoting Lenin, Alinsky wrote in Rules for Radicals, “They have the guns and therefore we are for peace and for reformation through the ballot. When we have the guns then it will be through the bullet.”

Alinsky also observed, “Utilize all events of the period for your purpose,” an idea reminiscent of Obama’s former Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel’s remark “You never want a serious crisis to go to waste.”

Alinsky’s chilling rules outlined in Rules for Radicals can be found here. Alinsky’s theories espouse Marxist and socialist ideologies, and this is the man on whom Hillary Clinton wrote her Wellesley College thesis. While writing her thesis at Wellesley on Alinsky’s theory of community organizing, Clinton met with Alinsky to have what she would later refer to as “biennial conversations.”

In her thesis, Hillary attempted to portray Alinsky as a mainstream American icon, writing, “His are the words used in our schools and churches, by our parents and their friends, by our peers. The difference is that Alinsky really believes in them.”

In the conclusion to her thesis, Clinton attempts to paint a rosier view of the ideologies Alinsky espoused:

Alinsky is regarded by many as the proponent of a dangerous socio/political philosophy. As such, he has been feared — just as Eugene Debs [the five-time Socialist Party candidate for U.S. president] or Walt Whitman or Martin Luther King has been feared, because each embraced the most radical of political faiths — democracy.

Her thesis showcases what is clearly a reverence for Alinsky and his views.

Still, Clinton did her best to downplay her relationship with Alinsky. In her memoir Living History, she references Alinsky just once when she indicates that she rejected a job offer from him in 1969 so that she could attend law school instead. She writes in that memoir that her intent was to follow a more conventional path.

Likewise, evidence that Clinton wanted to disconnect herself from Alinsky became clear when the White House had requested that Wellesley College seal her 1968 thesis from the public. But the publication of a 1971 letter from Clinton to Alinsky, and the response she received from Alinsky’s secretary, undermine any assertion that Clinton was not faithful to Alinsky and his ideology.

The letters were obtained by the Free Beacon news website and are part of the archives for the Industrial Areas Foundation, a training center for community organizers founded by Alinsky. According to the letters, Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals was earnestly anticipated by a young Clinton, who reached out to Alinsky in the summer of 1971 to ask,

When is that new book [Rules for Radicals] coming out — or has it come and I somehow missed the fulfillment of Revelation? I have just had my one-thousandth conversation about Reveille [for Radicals] and need some new material to throw at people. You are being rediscovered again as the New Left-type politicos are finally beginning to think seriously about the hard work and mechanics of organizing. I seem to have survived law school, slightly bruised, with my belief in and zest for organizing intact.

She added: “The more I’ve seen of places like Yale Law School and the people who haunt them, the more convinced I am that we have the serious business and joy of much work ahead — if the commitment to a free and open society is ever going to mean more than eloquence and frustration.”

Despite Clinton’s decision to attend law school rather than accept the job offer from Alinsky, she still remained a dutiful Alinskyite. Yet Clinton’s memoir claims that she and Alinsky somewhat parted ways over disagreements about how to bring about change, because her belief was that “the system could be changed from within.”

But that very notion is touted in Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals. “As an organizer I start from where the world is,” Alinsky wrote. “That means working in the system.” He added: “If the real radical finds that having long hair sets up psychological barriers to communication and organization, he cuts his hair.”

And even though Clinton rejected a job with Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation, she continued to endorse the organization’s efforts. According to a March 2007 Washington Post report: “As first lady, Clinton occasionally lent her name to projects endorsed by the [IAF]…. She raised money and attended two events organized by the Washington Interfaith Network, an IAF affiliate.”

A PDF of Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals can be downloaded for free by clicking here.

Photo of Saul Alinsky