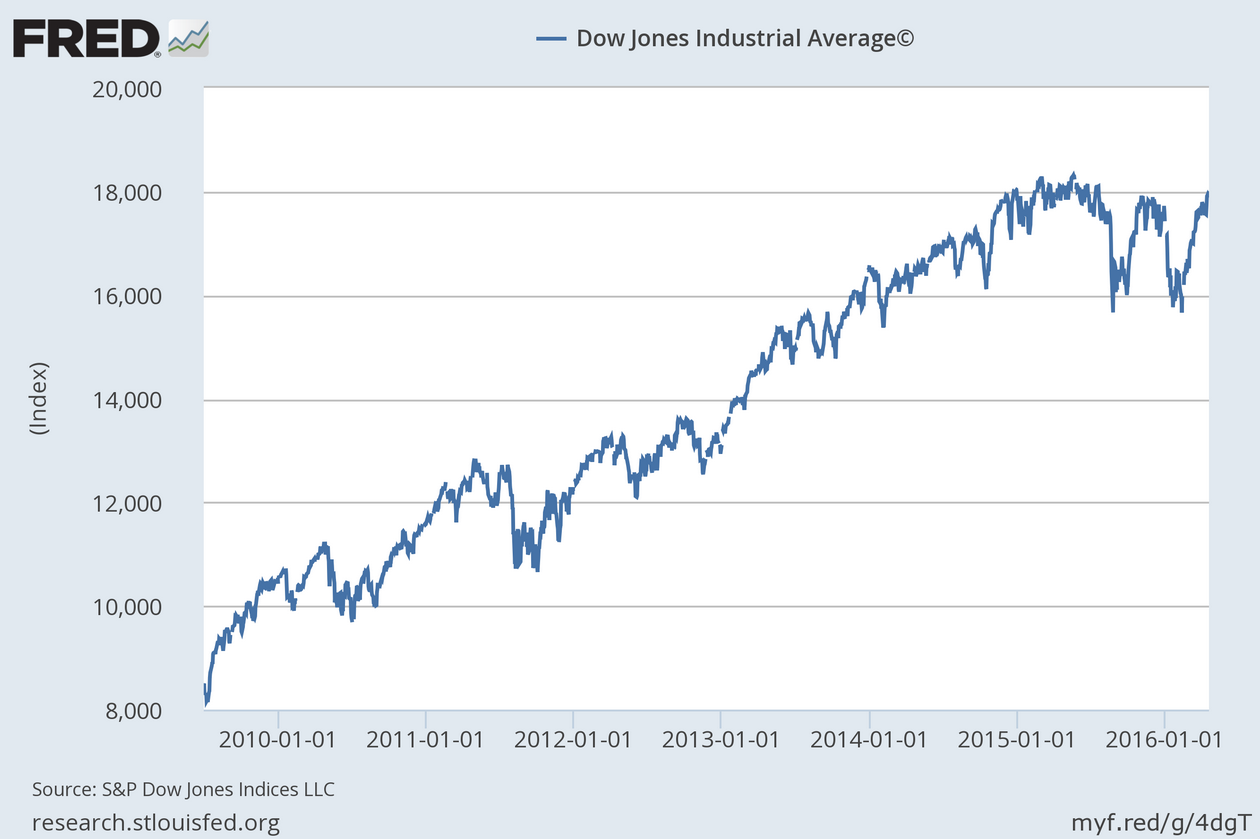

Despite the U.S. economy generating historically low growth since the end of the Great Recession, the stock markets have failed to take note. In fact, the opposite is the case: Since July 2, 2009, the Dow Jones has more than doubled in value, rising from 8,280.74 to Monday’s closing figure of 18,004.16.

Putting it another way, the economy has crept along at an annual growth rate of just over 2 percent, while the Dow has zoomed forward at an average annual increase of 18 percent — nine times as fast.

Is such a disparity sustainable? Some insist that it is, while others believe yet another asset bubble is on the verge of exploding — one that could sink the economy in the process.

In order to form an educated opinion, one must first take a look at the major factors influencing the stock markets.

Microeconomic Influences

Although the markets tend to be analyzed as entities, they are actually collections of individual companies, every single one with its own positive and negative influences. The list of influences includes the following factors:

• Profits/losses

• Dividends

• Positive or negative press

• Hiring increases or layoff notices

• Management changes

• New products/services

• Hitting or missing profit/growth targets

• Accounting errors or adjustments

These factors often explain why individual stocks rise or fall sharply even when the critical mass of the market is moving in the opposite direction.

Industry Issues

Even if an individual company is healthy, a decline in its industry can torpedo its numbers. In 1999, Eastman Kodak enjoyed revenues of approximately $14 billion and profits of $1.4 billion. Fifteen years later following the digital revolution, its net revenues had shrunk to $2.1 billion, with the company posting a $118 million loss.

Investor Sentiment

The phrase “a rising tide lifts all boats” holds true for stocks. Bull markets stoke investor confidence, which helps shift capital into the stock markets. The laws of supply and demand take hold, driving prices higher.

The opposite is also the case. When equity investors lose confidence, capital moves into alternative investments, depressing stock prices across the board.

Macroeconomic Factors

All else being equal, an economy that is growing and creating jobs serves as a catalyst for stocks to advance in value. So do low interest rates, as alternative options such as bonds, certificates of deposit, and other interest-bearing investments become less attractive.

Volatile factors such as inflation, deflation, the value of the dollar, the strength of the world economy, alternative investment options, political upheaval and sudden shocks to the system all play significant roles.

The Case for a Bubble

In the context of investments, Investopedia defines the term “bubble” as follows:

A theory that security prices rise above their true value and will continue to do so until prices go into free-fall and the bubble bursts.

The opening two paragraphs of this piece capsulize the heart of the “bubble” argument. Without question, values have risen more rapidly than the meager growth of the economy can justify. We not only see it happening in real time, but we know why.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, the Federal Reserve performed a series of maneuvers (Quantitative Easing I, II, and III, along with Operation Twist) designed to lower interest rates and massively expand the money supply. These interventionist steps spurred bank lending, consumer spending, business investments, and — given the loss of nearly $13 trillion of household wealth due to the recession — the rise of the stock market.

The Federal Reserve completed its final round of Quantitative Easing in 2014, and the bill has now come due. Short-term interest rates were increased by a quarter-point in December 2015, with further increases anticipated over the course of the next few years. The Fed is literally racing against time to normalize interest rates and the money supply without stoking inflation or tanking the economy in the process.

“Bubble” proponents see the Fed’s tightrope act as futile. There is simply too much money in circulation to avoid an eventual onslaught of inflation, a phenomenon that would likely cripple the recovery. Even if the economy avoids that fate, the next recession is on the horizon, as natural forces cause periodic contractions. Coupled with a change in the political landscape this November, the headwinds of uncertainty and upheaval will soon take the steam out of the stock markets.

The Case Against a Bubble

Detractors simply do not feel the odds are in favor of a “bubble” bursting. Furthermore, despite a few high-profile recent instances, they believe markets tend to act rationally.

Last October, Yale University finance professor William Goetzmann published a study entitled “Bubble Investing: Learning from History” in which he took a look at 41 stock markets around the world. Utilizing data as far back as the year 1900 to support his conclusions, he concluded there is just a 4.17 percent chance of a 50 percent+ decline following a strong bull market.

Speaking to rationality, a longstanding core principle taught by economists is that investors tend to act in their collective self-interests, which preclude inflating markets significantly beyond their sustainable limits. Corrections (defined as 10 percent+ decreases) release steam and rebalance values, preparing the markets for future growth.

Which One Is It?

While nobody knows that answer with certainty, it is undeniable that Federal Reserve intervention in has never been more heavy-handed. Cycles are substantially longer than they once were, and on average, growth is markedly slower. The money supply has ballooned out of control, while interest rates remain close to historic lows. The United States is experiencing its own variant of Japan’s “Lost Decade” of 1991-2000, and putting the genie back in the bottle has been as difficult for this country as it was for them.

Given that the rules of the game have obviously been re-written, the relevance of data going back over 100 years is, at best, highly questionable.

With respect to the efficient markets hypothesis, consider the following quote from Mark Rubinstein, finance professor at University of California, Berkeley in his paper entitled “Rational Markets: Yes or No. The Affirmative Case”:

When I went to financial economist training school, I was taught The Prime Directive. That is, as a trained financial economist, with the special knowledge about financial markets and statistics that I had learned, enhanced with the new high-tech computers, databases and software, I would have to be careful how I used this power. Whatever else I would do, I should follow The Prime Directive: Explain asset prices by rational models. Only if all attempts fail, resort to irrational investor behavior. One has the feeling from the burgeoning behavioralist literature that it has lost all the constraints of this directive — that whatever anomalies are discovered, illusory or not, behavioralists will come up with an explanation grounded in systematic irrational investor behavior.

As with anything worthy of debate, the readers are free to make their own conclusions. As philosopher/novelist George Santayana once wrote, “A soul is but the last bubble of a long fermentation in the world.”