The economic conventional wisdom of the moment is that the U.S. economy has begun to turn around. According to mainstream economists, a tentative recovery can be found in the third-quarter numbers, and in the drop in new unemployment claims from October to November.

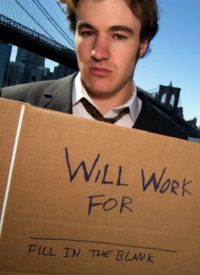

Tell this to the growing masses of unemployed people in Middle America, many of whom have been jobless for most of this past year and are suffering the traumatic shock of the downturn — as the air went out of the bubble that had developed and lasted up to December 2007.

A new New York Times poll documents the effects both financial and psychological that joblessness is having on those put out of work in the worst recession since the 1930s. The poll, conducted from December 5–10, surveyed 708 unemployed adults selected at random — many of whom, it is obvious, were caught completely off guard when the economy turned sour. In fact, the disruptions of people’s lives, and their children’s lives, has been at least as striking as records dating from the Great Depression itself — with the exception that the overall mood of the country was more optimistic about the nation’s future then.

The financial effects of long-term mass unemployment are striking. According to the poll, slightly over half have borrowed money from friends and/or relatives to meet basic expenses such as buying groceries. Over half have cut back on doctor’s visits or eliminated medical treatments they could no longer afford. Roughly a quarter have applied for or are receiving food stamps. A fifth have accepted food from a nonprofit or religious institution. Over half stated that they had cut luxuries and cut back on necessities to save money. Seven in 10 stated that their financial situation was bad or very bad.

Vicki Newton, a 38-year-old single mother from Mount Pleasant, Michigan, was interviewed following the poll: “I lost my job in March, and from there on, everything went downhill.” She had been working as a customer service representative for an insurance agency. She added, “After struggling and struggling and not being able to pay my house payments or my other bills, I finally sucked up my pride. I got food stamps just to help feed my daughter.” Eventually Newton abandoned her home, located in Flint, in the face of imminent foreclosure. She moved into a rental house owned by her father. Her story is hardly unique. High unemployment has taken foreclosures to record highs.

The effects of unemployment are not limited to personal and family finances. The psychological effects are bad as well. According to the poll, almost half admitted that they had begun suffering from depression or anxiety. A quarter of those who reported depression or anxiety had gone to see a mental health professional, although many are unable to continue with counseling because they cannot afford it or for other reasons, such as a car breaking down, they cannot afford to have repaired. Tammy Linville, a 29-year-old mother from Louisville, Kentucky, stated that she had been seeing a therapist for depression following the loss of her job as a clerical worker for the Census Bureau a year and a half ago. Medicaid had been covering her visits. When her car broke down and she could not afford to have it repaired, the treatments ended. She and her partner, who has been able to work sporadically at a local Ford plant, are "saving quarters for diapers" for their two small children, as she put it. "Everything I think about money, I shut down because there is none," she saide. "I get major panic attacks. I just don’t know what we’re going to do."

Almost half of those polled reported more conflicts between family members, or quarrels with friends. Fifty-five percent reported insomnia. A similar number spoke of feelings of shame or embarrassment — with the numbers higher for men, who are still perceived as society’s primary breadwinners. Many also noted behavioral changes in their children. They expressed fear of dropping out of their social class and ending up permanently impoverished.

More than half had lost their health insurance, which often came with employment. They described obtaining basic healthcare, when necessary, as a hardship.

Over two-thirds stated they were considering changing careers. Forty-four percent stated they had already begun retraining or enrolled in degree programs. Slightly over 40 percent noted that they had moved or were considering moving elsewhere to find work. It is true enough that some parts of the country have been hit harder by the recession than others. Some cities and towns are doing reasonably well, while others are turning into ghosttowns.

The unemployed are divided over who to blame. Twenty-six percent blame former president George W. Bush. Twelve percent blame the banks. Eight percent blame outsourcing or jobs going overseas, and eight percent blamed politicians generally. Just three percent blame President Obama.

They are more evenly divided over what the future holds. Thirty-nine percent stated that the economy would improve soon. Thirty-six percent expect things to stay the same. Twenty-two percent say the situation will get worse. While mainstream economists contend that recovery is imminent, they have covered themselves by adding that the recovery will be slow and that unemployment will remain high for some time to come. Of course, if people do not have money to spend in an economy, 70 percent of which depends on consumer spending, continued high unemployment will hamper any actual recovery in Middle America.

When evaluating these findings, it is important to keep in mind that the “official” unemployment statistic, which currently places joblessness at around 10 percent (down slightly from last month’s 10.2 percent), woefully underreports the full scope of unemployment in America. There are several measures of unemployment. Only one, U-3, is reported as the official unemployment rate. U-3 considers a person as unemployed only if the person is out of work and has sought work in the past four weeks. Those not meeting these criteria, which would include those who have enrolled in job training or degree programs, aren’t considered part of the labor force and so aren’t considered unemployed for statistical purposes. This sleight-of-hand results in a number that is somewhat more acceptable politically. The conventional unemployment rate also makes no distinction between those working full-time and those working part-time but would prefer full-time work.

A “broader” measure, U-6, counts as unemployed everyone counted under U-3 but adds “marginally-attached workers” and those working part-time who would prefer full-time work if they could find it. U-6 unemployment had reached 15 percent last March. Presently, U-6 unemployment stands at approximately 17.5 percent — over 70 percent higher than the official figure. According to John Williams of Shadow Government Statistics, even U-6 unemployment does not tell the whole story. What we may call SGS unemployment includes "discouraged workers" simply written out of the labor force by changes in methodology for counting the unemployed introduced by the Clinton administration in 1993. According to Williams’ figures, if "discouraged workers" are included in one’s count, the "real" unemployment rate in America rises to 22 percent!