“Surrender means that the history of this heroic struggle will be written by the enemy; that our youth will be trained by Northern school teachers; will learn from Northern school books their version of the war; will be impressed by all the influences of history and education to regard our gallant dead as traitors, and our maimed veterans as fit subjects for derision.”

Thus spoke Confederate General Patrick Cleburne near the end of the titanic struggle known variously as the Civil War, the War Between the States, the War of the Rebellion, or the War for Southern Independence.

As if to confirm General Cleburne’s prophecy, the Democratic-controlled House of Delegates and Senate in Virginia have now passed bills to repeal present state law, which has protected historic state monuments from removal or destruction. Instead, local governments would have the final say over Confederate-related monuments in their communities.

Governor Ralph Northam has announced his support for the legislation.

After the clash in 2017 in Charlottesville between alleged white supremacists and Antifa, there was a national wave of efforts to tear down Confederate-related monuments. In Virginia, however, state law forbade the removal of such monuments. Efforts to change that law were unsuccessful when Republicans had the majority in the Virginia Legislature.

But with Democrats controlling both the House and Senate, and the governorship, things have changed.

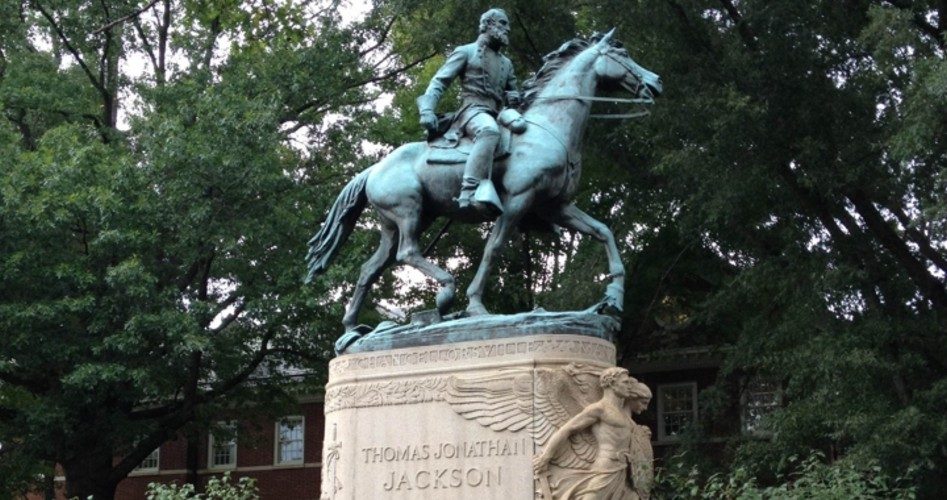

Virginia has well over 200 public monuments to Confederates, including those to famous Virginians Robert E. Lee and Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson.

Those who argue that the monuments should be removed say that they are offensive to African Americans because they romanticize the Confederacy and its supposed defense of slavery.

Just as General Cleburne predicted, the history of the Civil War has been distorted to fit a certain narrative. The war is usually presented as a simple morality play — the armies of the Union and the armies of the Confederacy just lined up to settle the whole issue of slavery. Slavery was certainly a point of contention between the sections, but it is unhistorical to say that the war was fought to abolish slavery.

What is true is that seven states seceded (left the Union in the final days of 1860 and the first few days of 1861), and that in all seven states slavery was an institution protected by law. But slavery was also protected by law in eight more states that remained in the Union. Only after President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress what he termed “the rebellion” in those seven states that four more states, including Virginia, seceded. They seceded rather than participate in Lincoln’s planned invasion of those seven seceded states.

Even then, Maryland, Missouri, Kentucky, and Delaware — four states where slavery remained legal — never seceded. If the Civil War was simply over the abolition of slavery, logic would dictate that Lincoln would have sent federal troops to those states for the purpose of freeing the slaves. On the contrary, both Lincoln and the Congress specifically said that the war’s purpose was to force the seceded states back into the Union — not to free the slaves.

General Lee inherited slaves from his father-in-law. Since he had to pay off the debts of his father-in-law’s estate, he kept the slaves for a short time, “renting” them out, then freed them as soon as those debts were paid. Lee freed them before Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation, at a time when it appeared quite possible that the South was going to win the war and its independence. Jackson owned no slaves, and, in fact, used his own financial resources to open a school for black children.

Yet, the bills passed in Virginia are based on the false notion that slavery was the issue being decided on the battlefield. The Senate and House bills are different, which means that those differences will have to be ironed out before Governor Northam can sign the legislation. The measure, as presently constituted, would stipulate that a locality would have to have a public hearing before any of its monuments could be removed. If they then voted to remove a monument, it would then have to be offered to “any museum, historical society, government or military battlefield,” leaving it up to the governing body in the locality to decide on its “final disposition.”

In other attacks on the state’s Confederate heritage, the state holiday honoring Lee and Jackson has been repealed, and a commission has been created to develop a replacement for the statue of Lee that Virginia had previously contributed to the U.S. Capitol.

Of course, when they are finished with cleansing Virginia of its Confederate symbols, next on the list of figures slated for removal will no doubt be other famous Virginians — Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and even George Washington.

Image: Nickmorgan2 via Wikimedia Commons

Steve Byas is a university history and government instructor and the author of History’s Greatest Libels, a defense at such great figures of history as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Christopher Columbus, Joseph McCarthy, and Warren Harding. He may be contacted at [email protected].