“There’s a segment of Native American students, that when they look at the art, to them it symbolizes an era of their history where land and possessions were taken away from them, and they feel bad when they look at them,” said University of Wisconsin-Stout Chancellor Bob Meyer, in explaining his actions to remove two paintings that have hung at the college since 1936.

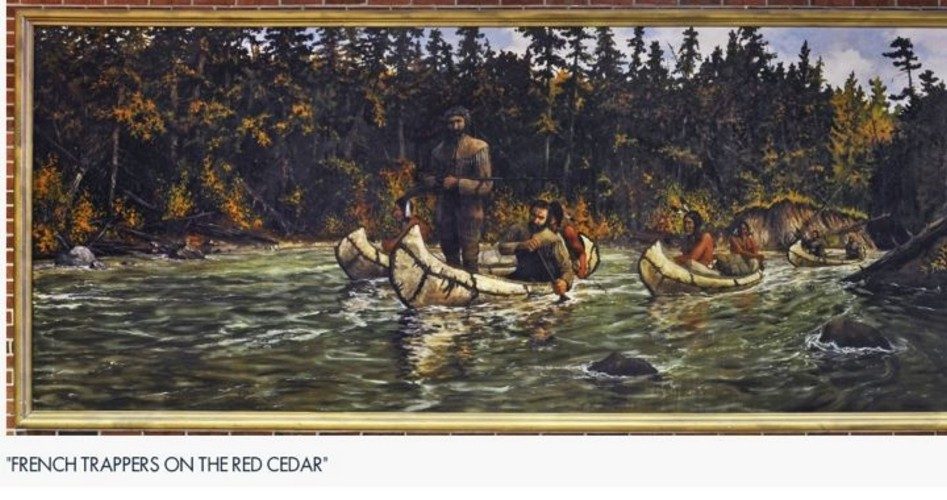

The paintings were a project of the Depression-era Works Progress Administration (WPA) — one depicting a French fort and the other showing French fur traders with Native Americans canoeing the Red Cedar River. Made by Wisconsin-born artist Cal Peters, they stand 6 feet tall and nearly 18 feet wide.

But some American Indian students have objected to the paintings, although they actually depict amiable relations between the French and the Indians. Historically, the French maintained a better relationship with the indigenous population than did many other Europeans, largely because, unlike the English, the French did not supply large numbers of settlers.

In addition to complaints by an undetermined number of Indian students, the school’s Diversity Leadership Team also weighed in against the paintings, warning that they could cause psychological problems among the Native students on campus. The team even claimed that the paintings perpetuated racial stereotypes.

So the paintings will be relocated from their present prominent spot in Harvey Hall to the dean’s conference room. Chancellor Meyer asserted that they were appropriate only for a “controlled gallery space,” where the right “context” could be presented for those who happened to see them. Hiding them away in a dean’s conference room is certainly “controlled,” but it could hardly qualify as an art gallery.

This has led some who support the paintings to accuse the school administration of bending to political correctness and censoring history. Meyer protested that he was not moving the paintings to be politically correct; rather, he said, it was a business decision:

So, we want to make sure that, really, what we decorate our hallways with and what we put in our hallways is consistent with our values to try to attract more Native Americans to the university.

Garyn Roberts, a university and college professor of 32 years at an unnamed school, responded in an online chat board to Meyer’s comments with some pointed observations:

Mr. Meyer is wildly uninformed. When does the book burning begin? Expanded history is great; revisionist history is the ultimate arrogance of the dangerously uninformed.

While leftists, Indian and non-Indian, tend to claim offense at any such portrayals of indigenous peoples, they appear to represent a minority viewpoint among Native Americans. For example, in a recent dispute over the use of the “Redskins” mascot in McLoud, Oklahoma, Summer Wesley, a Choctaw Indian and a lawyer, told the school board that the American Psychological Association believes all Indian mascots should be retired, because terms such as “Redskins” cause psychological damage to Indian children.

But at the same meeting, a student representing the McLoud High School Inter-Tribal Club spoke in favor of the Redskins mascot. She declared that outsiders such as Wesley “do not speak for our local native community. We are not being manipulated by others. We’re speaking out our own opinions. Not a single member of our tribal club find[s] the Redskin name offensive. We find the Redskin name … an honor.”

The Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, with its headquarters in McLoud, also issued a statement in support of keeping the Redskins mascot.

A recent poll published by the Washington Post revealed that 90 percent of Native Americans in every state said the term “Redskins” does not bother them. So why has there been such a push to eliminate Indian sports mascots in general, and the Redskin mascot in particular? Why do some seem to look for something to be offended by, such as a painting of a fort, or even a painting of several French traders and American Indians rowing down a river?

Part of the answer is that it has long been a leftist tactic, since at least the French Revolution, to divide society into antagonistic groups. Karl Marx, author of the Communist Manifesto, saw such a “class struggle” as a prime method for advancing the cause of communism. Thus, it is a common tactic of the Left to make use of existing animosities between different ethnic groups — and if such animosities do not exist, to create them. Young are pitted against the old; men against women; and the poor against the rich. Of course, charges of real or imagined racism even in benign paintings of several European traders and native people harmoniously interacting are often used to advance some element of the progressive agenda.

Such tactics serve to advance the goals of the Left, because the solutions are always more government control, in some fashion. In this case, the message is that if you do not like history, censor it.

As George Orwell once noted, “The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.” Liberals understand that they can win victories today by distorting the record of our past. Once the true history has been replaced, they can “create” a new history. Because, quoting Orwell again, “Those who control the present, control the past; those who control the past, control the future.”

Steve Byas is a professor of history at Randall University in Moore, Oklahoma. His book History’s Greatest Libels is a challenge to some of the unfair attacks on personalities in history, including Christopher Columbus and Marie Antoinette.