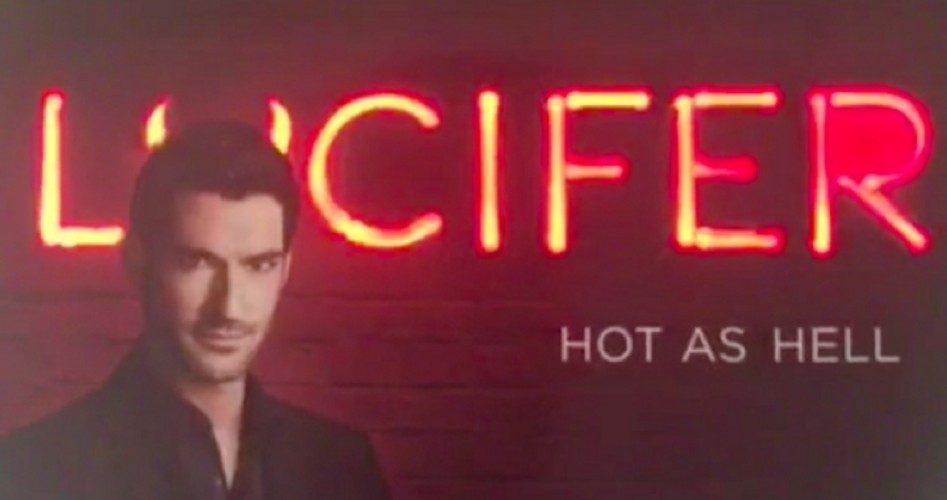

If late radio legend Paul Harvey were around to update his famous commentary “If I were the Devil,” he might include on his demonic to-do list, “portray Satan as a nice fellow.” Because this is precisely what the Fox network is doing in its new series Lucifer, set to premiere January 25.

Starring actor Tom Ellis as Lucifer, reviewer Valerie David writes that he is a “Brit-accented rogue helping humans while being harassed by angels” and that the show is “redemption for the Devil.” Deadline.com presents the storyline, reporting, “The series follow the story of the original fallen angel. Bored and unhappy as the Lord of Hell, Lucifer Morningstar (Tom Ellis) has abandoned his throne and retired to LA, where he owns Lux, an upscale nightclub. Charming, charismatic and devilishly handsome, Lucifer is enjoying his retirement, indulging in a few of his favorite things — wine, women and song — when a beautiful pop star is brutally murdered outside of Lux.” One thing leads to another, and Lucifer ends up helping the police solve crimes and working on the side of justice.

Not surprisingly, the show has inspired protests. The organization One Million Moms launched a petition urging Fox to scuttle the series, writing that it glorifies “Satan as a caring, likable person in human flesh.” And Natural News’ Ethan A. Huff minced no words, telling us, “The Lucifer character will be offered up to the masses who watch Fox as a likable character with moral and ethical convictions, fulfilling the biblical account of this insidious demonic entity…. It’s only fitting, then, that this modern-day show produced by satanists [sic] would portray Lucifer as a type of benevolent god, since this was always his goal — to take the place of the real God. Whether you believe what the Bible says or not, this is the clear-as-day implication of this upcoming show that will soon be watched by presumably millions of people.”

Of course, French poet Charles Baudelaire once wrote “The devil’s finest trick is to persuade you that he does not exist,” and many today scoff at the idea of Satan as real supernatural being. Even so, note that our culture considers the Devil symbolic of pure evil. As such, perspective is gained by analogizing this matter to something else symbolizing evil in our time: the Nazis.

Imagine a series portraying a “good Nazi” — with a character sporting the typical uniform and a Swastika — and billed as a story of “redemption for the Nazis”? Would we consider this innocuous entertainment or a blurring of the line between good and evil?

And that’s the point. While it seems unlikely that Lucifer’s producers actually are “Satanists,” they assuredly are moral relativists. And such a mindset suffices for evil’s embrace. Apropos to this, an old cartoon in what, if my recollection is accurate, was New Yorker magazine showed the Devil addressing a group of people in Hell and saying (I’m paraphrasing), “There’s no right or wrong down here. It’s whatever works for you.”

Topside in our temporal world, we hear similar messages such as “If it feels good, do it”; occultist Aleister Crowley’s maxim “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law”; and Obi-Wan Kenobi’s utterance in Return of the Jedi, “Luke, you’re going to find that many of the truths we cling to depend greatly on our own point of view.” British philosopher Edmund Burke warned that evil would triumph if good men did nothing. But why would we do anything (positive, anyway) if we consider good and evil mere social constructs, changing with “point of view”? And even if we had some vague sense that “ungood” exists, how could we know what to fight for and fight against with good and evil having been so conflated? Why, had Luke Skywalker truly taken Obi-Wan’s relativistic counsel to heart, he might have killed Han Solo and then become Emperor Palpatine’s PR man.

Yet black and white blended to gray is the norm today. Consider, for instance, the CBS program Angel from Hell, which One Million Moms (OMM) tells us is “about a ‘not so good’ guardian angel” and contains “blasphemous content including crude humor, foul language and distasteful dialogue.” In addition it shows the “angel” using profanity in front of children and “then joking that she never promised to be G-rated. The premiere also included the angel hiding liquor in the children’s clothes and saying, ‘My booze!’ followed by a little boy saying, ‘That’s so cool!’” writes OMM.

Or just contrast the original film Cape Fear (1962) with its remake (1991). About a lawyer targeted by a violent criminal he once sent to prison, the original portrays the attorney (Gregory Peck) as a truly virtuous man in the crosshairs of a wicked and distasteful miscreant, well played by Robert Mitchum. In the new version, however, the lawyer (Nick Nolte) is, frankly, a dirtbag. Cheating on his wife, he has a tumultuous, unappealing family life and is generally a weak man, the father every boy neither respects nor wants. In contrast, the criminal (Robert De Niro) is larger than life: He’s clever, smart, and exhibits superhuman mental strength, not even blinking at excruciating pain. In other words, the movie portrays no hero. And presented with a pathetic weak man and a powerful, cool super-villain, whom would teen boys be more likely to emulate? Hey, remember, you can’t really be “good,” anyway, because “good” is a social construct, just a “point of view.” But “power”? That’s certainly real — and alluring.

This is precisely the opposite of the moral training youths received for millennia and is frighteningly dangerous. It was always heroes who were imbued with superhuman qualities, including superhuman virtue (insofar as the civilization in question understood it), an example of such being Lucas McCain of the old show The Rifleman. And in presenting a strong, admirable character whom every boy would want to be and who was the embodiment of virtue, children would develop an “erotic [emotional] attachment” to virtue, as Plato put it, long before they were capable of understanding its moral components in their abstract form.

Today we’ve turned this on its head. By eliminating virtuous characters and portraying strong, manly ones who are the embodiment of vice, we inculcate an erotic attachment to evil. And “As the twig is bent, so grows the tree” — erotic attachments formed early usually last for life.

One thing Lucifer’s producers did get right is their casting of the main character as “hot as Hell,” as they put it, for the Bible tells us Lucifer is “perfect in beauty.” And therein lies a lesson for all: Beware those who would seduce with beauty, power, money, eloquence, sex — and all the other things that make for great Hollywood fare.