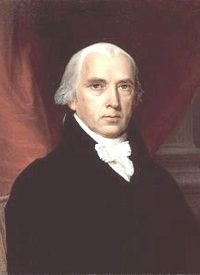

On June 8, 1789 James Madison, the congressman representing Virginia’s 5th District, rose to speak in a session of the First Congress and advocated passage of the slate of amendments to the Constitution to be known to history as the Bill of Rights. On December 15, 1791, the requisite number of states (three-quarters, or nine states) ratified the amendments and thus the Bill of Rights became the constitutional law of the land.

Between the lines of this brief, yet accurate, summation of the events that led to the passage of the first ten amendments are years of conflict, compromise, collaboration, and conviction. Conviction on the one side that without the protections afforded by an explicit Bill of Rights the national authority would march through such a gap and abridge the rights of the states and the people. The new national government would extend the limits of its influence and sovereignty into the territory of the state and the people unless some additional check was placed on that natural tendency, the so-called Anti-Federalists insisted.

The other side of the debate, however, argued that such an enumeration of rights was unnecessary because the new constitution granted no authority to the central government to commit such abuses. Besides, the Federalists contended, if a list of essential rights were written inevitably some right or other would be inadvertently left off the list and thus the national government would presume (perhaps) that such a right did not exist and, as the Anti-Federalists correctly pointed out, fill in that blank with oppression.

One of the chief opponents to the appending of such a roster to the recently ratified Constitution was James Madison himself. Madison, the Father of the Constitution, argued since the humid days of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 that a bill of rights was redundant as any rights now specifically enumerated in the Constitution would be retained by the people (as inherent in their natural right of self-sovereignty) or by the states as the intermediate expression of those rights.

As Madison explained it in his public pronouncements as well as in his private correspondence, a bill of rights was merely a “parchment barrier” and would not be a more effective barrier against tyranny than the robust federal system already established by the Constitution. In an extended republic, Madison argued, it would be the tension among the various factions and specifically between the states and the national government that would prevent the latter from usurping the rights naturally belonging to the former.

In spite of the strength and sway of his principles, James Madison was a man of extraordinary political sense. He unwaveringly believed that the Constitution he helped craft in Philadelphia was good and would establish a republican form of government that was dynamic in requisite ways and limited according to the immutable tenets of republican self-rule. With this in mind, Madison could not bear to see the fruit of this historic labor be thrown out for lack of a redundant restatement of rights.

Accordingly, James Madison set about advocating the passage of a bill of rights. Historians have rightly reckoned that without the tireless shepherding of the wise Virginian, the Bill of Rights would neither have passed through the First Congress nor been ratified by the states. Madison’s influence and acuity of understanding of the first principles of republicanism combined to give form to the panoply of protections set forth in the Bill of Rights.

The first of the essential liberties walled off from governmental encroachment by the Bill of Rights is that of religion. The First Amendment begins:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof;

The portion of that phrase preceding the comma is known as the Establishment Clause. The language after the comma is known as the Free Exercise Clause. Of particular note is the potential offender identified in this restriction: Congress. Ostensibly, therefore, this amendment affords no similar restrictions on the other two branches of the national government. Not, however, that this is a critical distinction, as the Congress is the only branch of government authorized by the Constitution to make laws (see Article I).

Together, these two clauses erected barriers around the right to worship (or not) and around the churches themselves. The Establishment Clause actually reinforced the Free Exercise Clause by preventing Congress from diminishing the scope of freely exercised dictates of conscience by officially establishing a national religion. The Congress could not discredit any one faith by endowing one or the other of them with the imprimatur of the state. Thus, all creeds were afforded equal protection. Of vital importance, however, is to note that the First Amendment requires no “wall of separation” be built between religion and government.

Freedom of speech is also protected from federal erosion by the First Amendment. It reads in relevant part:

Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press,

The Founders considered the freedom to speak an inviolable bulwark against the oppression of government of the governed. This right was, they believed, given to man by his Creator for the purpose of elevating discourse and improving the understanding of society at large. A key element of this right was the freedom from prior restraint; that is to say, free men in a republic did not need government’s permission to speak freely.

Freedom of the press was valued in equal manner as the freedom of speech. The Founding Fathers realized that government could be censored and corrected effectively through the press. There was in the press a particular power recognized for centuries both to praise and pillory in a manner that was most conducive to restraining the abuses of elected officials and reminding the electorate of the laws being passed on their behalf.

The precise nature of the rights protected by the Second Amendment have been debated for decades. The Second Amendment reads:

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Our Founding Fathers considered the right of a person to defend himself and his home against invasion, as well as the right of a citizen to resist the rise of tyrants, as one given to him by nature. No man had the right to divorce another man from his right of self-defense, whether the attack be made on his home or his country. Regardless of the intent of our Founding Fathers, the Second Amendment continues to be targeted by those who rightly sense the power of the people to mount armed resistance to tyranny. By the plain language of the Second Amendment, the Congress is prevented from infringing in any way the absolute right of a free people to keep and bear arms in defense of themselves, their families, and their freedom.

The Bill of Rights protects numerous other vital rights from congressional dissolution. The right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures (4th Amendment); the requirement of due process before life, liberty, or property may be taken; the protection from the taking of property without just compensation (5th Amendment); the right to a speedy trial (6th Amendment); and the right to a trial by jury (7th Amendment), among others. They are each a palladium of liberty reminding us and all men of the unalienable rights granted us not by government, but by God.

Finally, we turn to the timely topic of the Ninth and Tenth Amendments and the metes and bounds thereof. Once Americans had withdrawn from the British Empire via the Declaration of Independence, we returned to a sort of “state of nature.” In this state the people were in absolute possession of the full panoply of natural rights by which they were “endowed by their Creator.” Upon finally and fully dissolving the ties that bound them to the Crown, Americans were free to enact state constitutions wherein they ceded some of those rights to a state government.

Next, upon creating the Constitution of 1787, those sovereign states in turn granted some of their power to the new national government. Summarizing the legislative history of the Ninth and Tenth Amendments, Professor Robert Natelson writes:

The Ninth and Tenth Amendments were both rules of construction without substantive force of their own. The words “rights” and “powers” in the two provisions were essentially interchangeable. The Ninth Amendment reminded the reader that although the Constitution created exceptions to some federal powers, it limited federal powers in other ways, too. The Ninth Amendment implicitly acknowledged that the federal government had implied, incidental powers, but warned the reader not to construe them too broadly. The Tenth Amendment embodied a similar caution about construing powers too broadly. The Tenth Amendment also reminded the reader that the designatio unius maxim applied to the Constitution’s enumerated powers, and expressly excluded the theory that the federal government enjoyed unenumerated powers arising from “inherent sovereign authority.”

All of the liberties protected by the Bill of Rights are in danger. Designing lawmakers stretch some clauses on the rack of statism, while the critical freedoms safeguarded by the first ten amendments are regularly and ruthlessly ignored and abrogated. In this regard, as in so many others, Publius (Alexander Hamilton, in this case) proved prescient when he warned in The Federalist:

I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and to the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed Constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers not granted; and, on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Why, for instance, should it be said that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which restrictions may be imposed? I will not contend that such a provision would confer a regulating power; but it is evident that it would furnish, to men disposed to usurp, a plausible pretense for claiming that power. They might urge with a semblance of reason, that the Constitution ought not to be charged with the absurdity of providing against the abuse of an authority which was not given, and that the provision against restraining the liberty of the press afforded a clear implication, that a power to prescribe proper regulations concerning it was intended to be vested in the national government. This may serve as a specimen of the numerous handles which would be given to the doctrine of constructive powers, by the indulgence of an injudicious zeal for bills of rights.

It is aphoristic that if one gives another an inch, he will take a mile. In the case of the national government, however, it then will proceed to argue about the applicable length of an inch and a mile and whether or not such measurements are necessary anyway. (See this video.)

Foes of liberty in the legislative branch are aided and abetted by willing accessories on the bench of the Supreme Court. In a series of cases, the justices of the land’s highest court have issued rulings that are an unjustifiable demonstration of jurisprudential gerrymandering. In these holdings, the Court has wielded the well worn shears of judicial activism and has shredded Madison’s “parchment barrier.” The Bill of Rights is divided (bifurcated) into two lists: those rights which are “fundamental to the American scheme of justice” and those which are, one deduces, expendable.

There can be no serious debate as to whether or not the national government has repeatedly attempted to eradicate the boundaries placed by the Bill of Rights around its power — it has. From the beginning, our elected representatives have overstepped the limits drawn around their rightful authority and have passed laws retracting, reversing, and redefining the scope of American liberty and state sovereignty. Our sacred duty is to tirelessly resist such advances and exercise all our natural rights to restrain government and keep it within the limits set by the Constitution.

We, the People, are the ultimate sovereigns in this Republic and the Constitution does not grant rights, it simply protects them. And it will do so only to the degree that we in turn hold it inviolate and demand that its strictures be observed by those who have sworn to uphold it.

Graphic: James Madison