Most educated Americans have heard of “Pavlovian response.” This term comes from experiments by Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov, who demonstrated that certain responses can be conditioned in dogs — and, supposedly, humans.

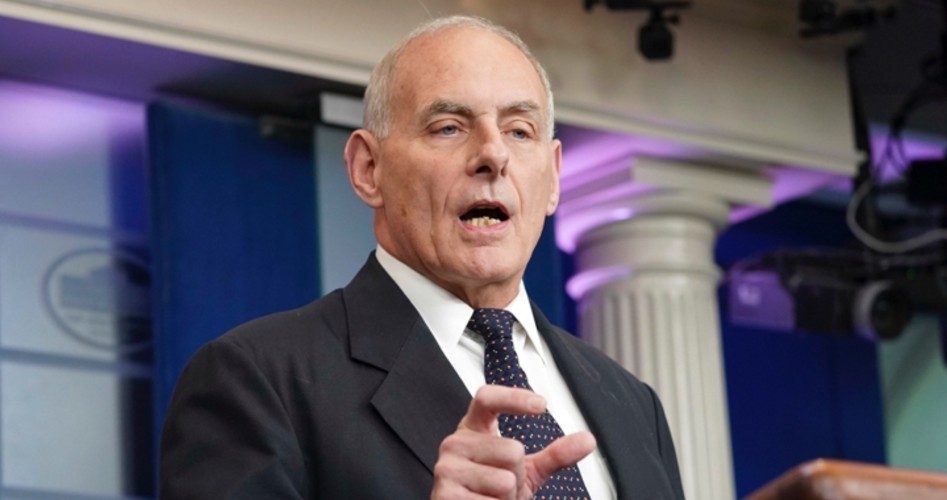

The reactions to White House Chief of Staff General John Kelly’s (shown) remarks on Monday nights’ Fox show, with host Laura Ingraham, are an example of how even the names of certain historical figures, and remarks about historical events, can trigger what could be called a “Pavlovian response.” Responding to Ingraham’s question about the recent decision of an Episcopal church in Virginia to remove plaques honoring Confederate General Robert E. Lee and George Washington (once parishioners of that church), Kelly called Lee “an honorable man.”

It was rather predictable that every action and statement of Kelly would be carefully scrutinized by the liberal establishment (media, popular culture, and academia) in attempt to destroy his reputation. From the day that he came to President Donald Trump’s defense for Trump’s choice of words in calling and attempting to console the widow of a soldier who died in Niger, the Left has had Kelly in its crosshairs.

Kelly told Ingraham, “I would tell you that Robert E. Lee was an honorable man. He was a man that gave up his country to fight for his state, which 150 years ago was more important than country. It was loyalty to state first back in those days. Now it’s different today.”

Of course, the name of Lee is now “associated” with slavery and secession in the public mind, because Lee was the leading general in the Confederate army. To most Americans, all they “know” about the Civil War is that it was “fought to end slavery,” or that it was “about slavery.” The “Pavlovian response,” if you will, is that Kelly was arguing that slavery was honorable, an interpretation only possible by those who have been conditioned to think Lee and all other southerners were simply fighting to save the institution of slavery.

Actually, the Civil War was fought to force southern states that had seceded back into the Union. Had it been fought to abolish slavery, then President Abraham Lincoln would have sent federal troops into Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and Delaware, to “free” their slaves. Those were four Union states where slavery remained legal until the 13th Amendment was passed in 1865.

“Today our country is trying to once again come to grips with the history of slavery,” read a portion of the statement from the Virginia church that took down the plaques of Lee and George Washington. The church’s statement said it was necessary to remove the plaques because they made “some in our presence feel unsafe.” Unsafe? What did they think the plaques were going to do? Jump off the wall and attack them?

Apparently, the fact that both Washington and Lee had once owned slaves makes them forever unworthy of honor. Washington freed his slaves, having come to oppose the institution. So did Lee, who had inherited some slaves from his father-in-law. In fact, Lee wrote to his wife before the Civil War, “I believe in this enlightened age, there are few who will not acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil.”

Following the war, Lee displayed kindness not only to fellow Confederate veterans, but also Union veterans. He also took a leadership role in an effort to get his fellow southerners to respect the dignity of the former slaves. When other members of an Episcopal church in Richmond were hesitant to take communion with a black man in the church, Lee stepped forward to do so.

Lee was not defending slavery by taking command of the Army of Northern Virginia. He fought because his state of Virginia was invaded by Union troops, and he could either fight with his fellow Virginians, or against them. Like Lee after freeing the slaves he inherited, the average Confederate soldier did not own slaves, but was fighting simply to defend his home against invasion. Why would a Confederate soldier die so his neighbor could have slaves?

Kelly told Ingraham that a “lack of ability to compromise led to the Civil War.” This remark was also attacked, although it is clearly just a statement of fact. It is not a judgment of which side was right or wrong, but if there had been a compromise (as happened in previous controversies between North and South, settled by the Missouri Compromise, the Tariff Compromise, and the Compromise of 1850), there would have been no war in 1861. Whether that was the desired outcome — no war — is a value judgment, but the fact is that most wars result when the two belligerents have failed to compromise.

But, of course, General Kelly’s comments are seen as “controversial,” largely because so many Americans are dismally ignorant of the Civil War. Over 600,000 men, wearing both blue and gray, died in the Civil War, with Union soldiers mostly fighting to “save the Union,” and Confederate soldiers mostly fighting to repel an invasion of their homeland.

The reactions to Kelly’s remarks tell us more about his detractors than it tells us about him.

Photo: AP Images

Steve Byas is the author of History’s Greatest Libels, in which he challenges what he regards as some unfair attacks upon historical figures.