The Liberty Institute has come to the defense of a five-year-old Florida student who was scolded by a school lunchroom supervisor and prevented from praying over her noon meal. The conservative legal advocacy group sent a strongly worded letter to officials at the Seminole County School District and Carillon Elementary School in Oviedo, Florida, on behalf of Marcos Perez, who removed his five-year-old daughter from the school after she was accosted by the lunchroom supervisor and told to stop praying over her lunch.

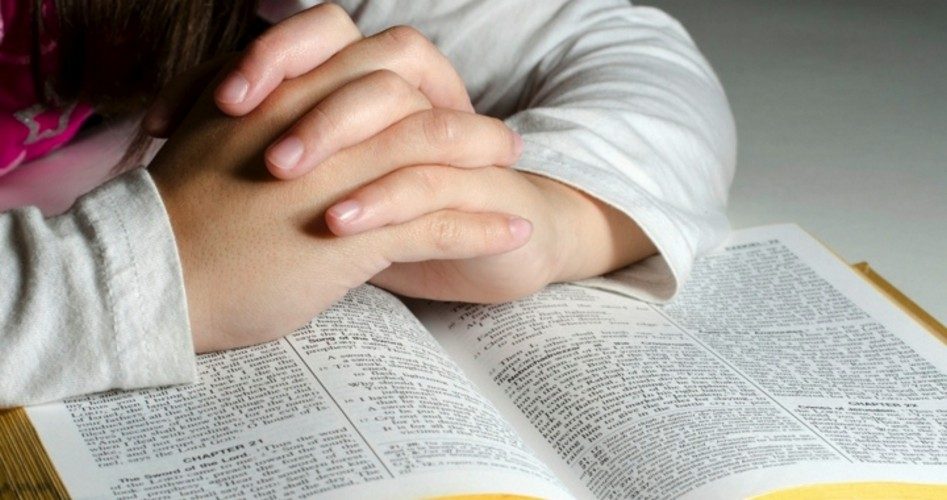

According to Jeremiah Dys, senior counsel at Liberty Institute, on March 10, as the kindergartener was bowing her head in prayer for her lunch at school, the lunchroom supervisor approached her and told her to stop. When the youngster protested, “But it’s good to pray,” the adult responded that “it is not good.”

When the girl once again attempted to pray over her lunch, related Dys, “she was again restrained from bowing her head, folding her hands, and silently saying grace.”

The girl’s father said that the disturbing incident prompted him and his wife to pull their daughter from the school and teach her at home. “Mainly because of this incident, we have exercised our option as parents to teach our daughter at home,” said Marcos Perez. “We live in a very good school district, but we cannot, in good conscience, send our daughter to a school where her religious liberty has been compromised.”

The incident also launched the Liberty Institute into action, with Dys shooting off a letter to school officials demanding that the district “apologize to the Perezes and the community as well as take steps to ensure this does not happen again.”

“Of course, students can pray at school!” said Dys in a prepared statement, noting that the Supreme Court ruled over 50 years ago that students do not sacrifice their constitutionally protected right to freedom of speech or expression when they enter the classroom.

“It is a foundational principle of American jurisprudence that the First Amendment protects the religious liberty of students in America’s public schools,” Dys noted in his constitutional tutorial to officials with the Seminole County School District.

“Just because a lunchroom supervisor … may not agree with the practice of prayer does not give this supervisor the freedom to insert the state’s beliefs for that of the student,” wrote Dys.

Dys cited the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1969 landmark ruling in Tinker v. Des Moines, which found that public schools “may not be enclaves of totalitarianism.” The High Court explained that school officials “do not possess absolute authority over their students. Students in school as well as out of school are persons under our Constitution. They are possessed of fundamental rights which the state must respect, just as they themselves must respect their obligations to the state…. [Students] may not be confined to the expression of those sentiments that are officially approved.”

Dys concluded his epistle by warning of further action against the school district if it does not “issue a public apology for this instance of religious discrimination and announce the steps it is taking to ensure this does not happen in the future.”

For its part, the school district apparently dismissed the incident as fictional. “The situation as stated by the parent has not occurred according to the school’s investigation,” Michael Lawrence, a communications officer for Seminole County Schools, told local TV station WKMG. “We’re dealing with very young children here, so there’s quite a bit of an opportunity for miscommunication to occur.”

In a similar case last fall, the Liberty Institute represented a 10-year-old Tennessee student who was prohibited from writing an essay citing Jesus as her hero. That case prompted the Tennessee legislature to pass a religious freedom bill for students throughout the state.