“He’s personally my favorite teacher in the whole school,” Ana Kneisely told CBS Sacramento, in reference to a middle school American History teacher, Woody Hart, in Rancho Cordova, California, who was forced to retire by the Board of Education.

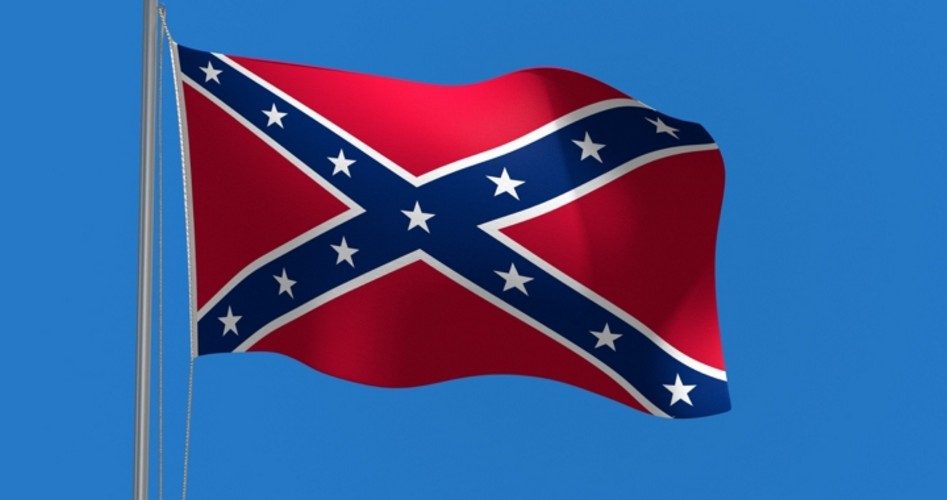

Hart, a 70-year-old teacher at Suttle Middle School of the Folsom Cordova United School District, was ousted after using a Confederate battle flag, along with a period United States flag, as part of a lesson on the U.S. Civil War. The school’s superintendent, Deborah Bettencourt, released a statement late last week that the board of education had “accepted this Sutter Middle School teacher’s retirement … and he will not be returning to school this year.”

In an interview with the local CBS affiliate, KCRA, Ana Kneisely, one of Hart’s students, explained what had happened. “We just came in and we saw the Union Flag on one side of the room and the Confederate Flag on the other side of the room.”

Apparently, this was typical of the way Hart taught. “I actually very much appreciated the way he taught history,” Kneisely said. “I felt that we were getting more involved than what our other classes did.”

For example, Hart used the two flags of the opposing sides in the Civil War to create interest. The two hanging flags were part of Hart’s lesson, as students were members of one of the two armies.

Kneisely added that she did not understand why Hart’s display of the flag of one of the two sides involved in the war was controversial, considering that the flags, including the Confederate flag, are also used in the textbook for the same purpose.

Back in November, a black family filed a complaint against Hart for his remarks, in which he explained the unfair way blacks were treated during segregation. Hart told his students that, at one time, some Southerners responded to calls for “black equality” with disdain, saying terrible things such as, “We treat all black people equally. We hang them all.”

The Sacramento chapter of a group calling itself Showing Up for Racial Justice also weighed in, demanding a public apology from Hart.

Apparently, Hart was only relating historical incidents in which people went to the South during those days to promote better treatment and equal rights for blacks, only to be told that they do treat blacks equally — they hang them if they are in-state African-Americans, and they hang them if they are visiting African-Americans. Hart was simply telling the students how terribly blacks were far-too-often treated during that time.

And, with the Confederate battle flag, Hart was teaching his class accurate history as to the use of the flag — in battles during the Civil War.

But the school district argued that it did not really matter how the flag was used during the Civil War; it should not be seen by students today. “We recognize that regardless of context, to many of our students, families, and staff, the Confederate flag is a racist symbol of hate. Although this matter is under investigation, it is important to reiterate: Any employee who is found to engage in behavior that creates an unsafe environment for students will face full consequences, including the possibility of initiating termination proceedings.”

Bettencourt, the superintendent, said that the district’s action did not mean that they were attempting to “limit the free speech of our teachers.” Then, in an Orwellian addition, she stated that she expects “teachers and staff will do this work using culturally appropriate strategies.”

The district statement added, “It is our schools’ responsibility to provide a safe learning environment for all children.”

It is not clear how the display of a flag, which was actually used in many battles during the American Civil War, creates an unsafe learning environment for children. And, exactly what is meant by “culturally appropriate strategies?”

The obvious meaning is that certain events and symbols in history are to be censored — or as George Orwell described it in his classic dystopian novel 1984, some things should be disposed of in the “memory hole.”

Among those things that should be relegated to the “memory hole,” and not even shown to students (because it apparently would make them “unsafe”), is a Confederate battle flag. Since the murders inside a church in South Carolina, in which the killer posted photographs of himself on Facebook along with the flag, there has been an intense offensive against any public display of the historical flag.

Critics contend that the flag is nothing but a racist symbol in a war allegedly fought over slavery, and in more recent times, as a symbol used by racist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. But champions of the flag have countered that the flag is simply a symbol of Southern culture, and that slavery was not the issue over which the Civil War was fought.

Sometimes called the “Southern Cross,” the flag was a variation of the flag of Scotland. It was actually a Christian symbol, a St. Andrew’s cross, with white stars added to a red field. An extremely large number of southerners were descended from Scottish and Scots-Irish families, and the flag represented the warrior culture of Americans of that ethnic strain. It was never the official flag of the Confederate States of America (CSA), but rather a flag to be used on the battlefield. It was made famous by the Army of Northern Virginia, under the command of General Robert E. Lee.

The original national flag of the CSA was dubbed the “Stars and Bars,” and was used until 1863. At the Battle of First Manassas, or Bull Run, this flag caused confusion, because with the smoke and dust of battle, the two opposing armies often confused each other’s flag.

Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard, who was in command of Confederate forces at Manassas, the first great battle of the war, suggested adopting a different flag, to be used in battle, to avoid such confusion. While this was eventually done, the Confederate Congress never formally adopted it for use, but used other flags for the Confederate government.

But it was used — that is a historical fact. But some historical facts, apparently, should be erased from the history books and history classrooms of this country — at least according to this school district in California.

The action by this school district raises the question of whether we are to censor history and eliminate certain events and symbols from our collective memory. True historians convey history as it was — the good, the bad, and the ugly — because to do otherwise is simply telling a lie. The very reason we study history is to learn lessons from the collective memory of the human race, both the living and the dead. If certain things are to be excluded from that collective memory, we have crippled ourselves from using the study of history in its proper way.

Unfortunately, such censorship of historical facts is not unique to this one school district in California (although one suspects that in that state, it is probably more common than in most others). Today, it is the Confederate battle flag which is to be blotted out from the historical record, because its detractors argue it has been used by racists such as the KKK. Actually, if one examines photographs of Klan rallies, more United States flags are used than Confederate battle flags.

And what are we to do with the Klan practice of burning a cross on someone’s lawn? Should the Christian cross be consigned to oblivion, as well? One suspects there are many who would like to do so, using whatever excuse that they can.

While I teach history at a Christian liberal arts college (Randall University in Moore, Oklahoma, run by the Free Will Baptist denomination), I began my career many years ago in a small, rural school district in Oklahoma. The principal sat in on my World History class one day when I was covering the Medieval Church. (The church was a powerful and important institution in the Europe of the Middle Ages, and the textbook devoted a whole chapter to it).

Later, he cautioned me to “be careful.” He suggested it might be better to not mention the Roman Catholic Church of the Middle Ages, as that might offend someone. At first I laughed, thinking he was joking. But he was not. He was concerned that teaching what the Church taught and did in the Middle Ages might even constitute government establishment of religion.

It was a comment so odd that I was unsure what to say, but it would be comparable to teaching the American Revolution without mentioning George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams, or teaching about Richard Nixon without mentioning the Watergate Scandal.

Can one imagine teaching about Adolf Hitler, and not mentioning the Holocaust?

Or, perhaps it would be like teaching a group of middle school students about the battles of the Civil War, and refusing to use a photograph of a Civil War battle because it happened to include a soldier holding a Confederate battle flag. Horrors!

After all, they might feel unsafe.

Steve Byas is an instructor of history and government at Randall University, in Moore, Oklahoma. His book History’s Greatest Libels is a challenge to some of the misrepresentations of history concerning such individuals as Christopher Colombus, Marie Antoinette, and Joseph McCarthy.