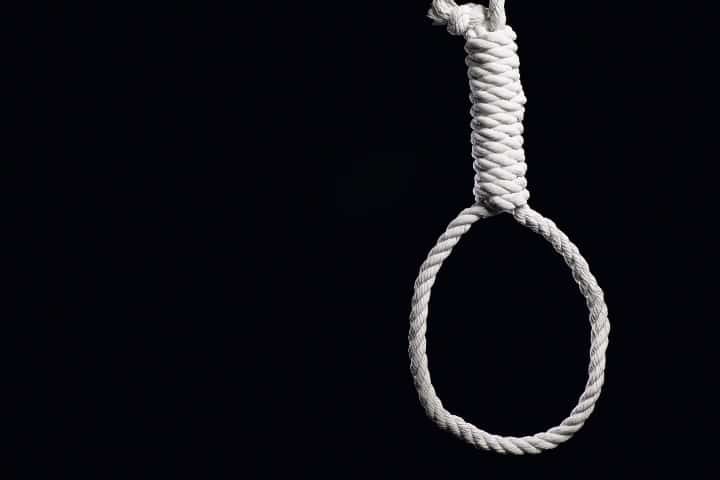

SINGAPORE — In June and September of 2022, Malaysia affirmed that it would abolish the mandatory death penalty, which was used for crimes such as murder and “terrorism.” Instead, the country decided that it would leave suitable punishment measures for such crimes to the discretion of judges.

Malaysian authorities reviewed the findings of a report on suggested alternatives to the death penalty, and have indicated that they would consider alternatives to the mandatory death sentence, Law Minister Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaffar announced in a statement. The country will also examine the use of the death penalty for 22 other offenses.

Junaidi confirmed that the authorities’ decision was made following a spate of discussions held on Sept. 6 and 13, according to Channel News Asia reports on Sept. 14.

Along with prominent members of government agencies who concurred with the proposal to replace the sentences for 11 offenses that carry the mandatory death penalty, Junaidi spearheaded the discussions of the Substitute Sentences for the Mandatory Death Penalty Task Force Technical Committee.

The minister emphasized his views on replacing the death penalty with new punishments that match the gravity of the crime.

“I remain committed to fighting for fairer and compassionate laws on the issue of whipping and the death penalty,” Junaidi affirmed in a Facebook post.

The Southeast Asian country first began working to abolish the death penalty in October 2018, under the Pakatan Harapan government.

The number of people on death row at that time exceeded 1,300 people, based on local media reports, and most of them were arrested for drug offenses.

Although Malaysia announced a moratorium on executions in 2018, laws enforcing the death sentence endured so courts had to enforce the mandatory death sentence on convicted drug traffickers. Other crimes, notably rape resulting in death, terrorist acts, and murder, also would incur the death sentence.

Based on a recent Amnesty International report about global executions, no executions took place in Malaysia in 2021.

“As of 12 October [2021], 1,359 people were under sentence of death, including 850 with their death sentences being final and appealing for pardon and 925 convicted of drug-related offenses,” the report indicated. Out of the 1,359 sentenced to death, 526 were foreigners, it highlighted.

Various groups applauded the country’s latest decision, declaring that it was an “important step forward” for the country and region.

“Malaysia’s public pronouncement that it will do away with the mandatory death penalty is an important step forward — especially when one considers how trends on capital punishment are headed in precisely the opposite direction in neighboring countries like Singapore, Myanmar, and Vietnam,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director of Human Rights Watch. However, he added, “Before everyone starts cheering, we need to see Malaysia pass the actual legislative amendments to put this pledge into effect.”

The Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network (ADPAN) similarly welcomed the move, elaborating in a statement that the death sentence “does not provide justice as it deprives judges of the discretion to sentence based on the situation of each individual offender.” ADPAN urged further reforms in the criminal justice system, such as a redefinition of drug cases in order to better distinguish between drug mules and actual traffickers.

Notably, Junaidi’s statement didn’t say when Malaysian authorities would wrap up their examination of alternative forms of punishment. Neither did he provide hints as to what these amendments might entail.

Like its neighbor Malaysia, Singapore, has also had strict drug laws such as capital punishment for traffickers, and in light of Malaysia’s recent abolishment of the death penalty, pressure has been put on Singapore’s authorities to follow suit.

However, even amid international pressure, Singaporean authorities have maintained an unwavering stance on maintaining the death penalty in the tiny city-state of more than five million residents.

When questioned about what it would take for Singapore to examine its stance on the death penalty, Singapore’s Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam said in a Sept. 14 interview with Bloomberg that by maintaining the death sentence, the Singapore government would be acting in the best interests of society.

Shanmugam highlighted that the deterrent effect of the death penalty against drug trafficking has saved — and would continue to save — thousands of lives, saying:

In the 1990s, we were arresting about 6,000 people per year. 30 years later today, there are more drugs around the region. Singapore is wealthier. Afghanistan and Myanmar are among the largest producers of drugs in the world. We are a logistics centre. We would be completely swamped. The UNODC [United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime] said that this place is swimming in meth and a record haul of one billion meth tablets were seized in Southeast Asia. We are in that situation.

The minister bolstered his argument by stating that, as of 2021, more than 65 percent of Singaporeans supported the mandatory death penalty. He continued:

But … what’s the task of the Government? It is to do right by Singaporeans, what’s in the best interest of society. [We believe] that the death penalty, in fact, saves thousands of lives, because of its deterrent effect. And I can show you examples from all the other countries which don’t have the death penalty, and lacks enforcement on drug policy, thousands more people die.

Based on media reports, Singapore has executed ten people so far in 2022 for drug trafficking, and the courts have dismissed last-minute appeals from death-row inmates in recent months.

For instance, Singapore proceeded with the high-profile execution of Nagaenthran Dharmalingam, a Malaysian with learning disabilities. Dharmalingam’s case garnered global interest and various appeals for clemency from his family, United Nations officials, the European Union, and the Malaysian government.

In June this year, Shanmugam reiterated to the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) his conviction that the death penalty is the right policy to tackle drug trafficking, highlighting “clear evidence” of it being a serious deterrent for would-be traffickers.

He also alluded to an anti-death-penalty protest that took place in Singapore in April this year in response to talk about a “groundswell” against Singapore’s death penalty, encouraged by news reports, activists, and notable personalities like British entrepreneur Richard Branson.

While protest organizers claimed that attendance of the event exceeded 400, Shanmugam contested such claims. He continued:

Now, therefore, if we believe that it is the best interest of society, Singapore, and if the vast majority of Singaporeans support it, as they do, then do you want us to change policy because four newspapers write about it, talking to the same three activists and quoting the same three activists?

And I’m not saying these are precise numbers, but I’m giving you the picture. So, the government policy, if 400 people plus three newspaper articles can change government policy, or if Mr Richard Branson can change government policy, then Singapore would not be where it is today….

But by and large, a vast majority of Singaporeans understand that drugs are bad, drugs are bad for society.

There is a small group that thinks that it ought to be legalized. And because of the portrayal in popular media, younger people, not the majority, tend to have a slightly different view of cannabis and these are all challenges we have to deal with.

When questioned if the authorities’ firm stance towards countering drug trafficking would translate into stricter regulations and “closer surveillance” of people coming into the country from countries like Thailand and Malaysia, Shanmugam replied that Singapore’s current measures are “adequate.”

“But the laws, the amount, the kind of evidence that is needed, the assumptions or presumptions that apply, the inferences the courts can draw, these are technical matters, and they are constantly reviewed,” he said.

“And, you know, we have amended the law a number of times and we will amend it as we see necessary.”

A survey from 2019 conducted by Singapore’s Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) displayed “very strong” support for the death penalty, Shanmugam said.

Citing data from the MHA demonstrating a decrease in the amount of cannabis and opium trafficked into Singapore in the four years following the introduction of the mandatory death penalty for trafficking more than 1,200 grams of opium and 500 grams of cannabis in 1990, Shanmugam further substantiated his claim about the effectiveness of the death penalty.

He noted that places that have legalized drugs or taken a softer stance towards them have fared comparatively worse than Singapore, and contrasted his country’s relatively drug-free culture to that of American cities like San Francisco and Baltimore, which are known for rampant drug use.

A separate MHA study in 2021 on people hailing from regions where most of Singapore’s arrested drug traffickers have come from in recent years also revealed that Singapore’s death penalty significantly deterred them from committing drug-related and other major crimes in the country.

For instance, 82 percent of respondents from the region felt that the death penalty deterred people from engaging in serious crimes in Singapore. Also, 69 percent of respondents felt that, as compared to life imprisonment, the death penalty more compellingly discouraged would-be offenders. And an overwhelming 83 percent of respondents opined that the death penalty deters people from trafficking considerable amounts of drugs into Singapore.

Shanmugam commented on the survey:

I emphasise this: These are the places from which many of our traffickers have come from. You remove the death penalty, that number, 83 per cent, will surely be reduced because there is money to be made.

It’s a fair assumption to say more people will traffic drugs into Singapore, more drugs will enter into Singapore, there will be more drug abusers in Singapore, and more Singaporean families and individuals will be harmed … It’s a stark choice for Singaporeans.