Are the days of the European Union coming to an end? The riots in Athens, the popularity of the True Finns Party in Helsinki, and the growing tension between Paris and Berlin all indicate that more and more Europeans are seeing themselves as citizens of nations, rather than members of an amorphous bureaucracy headquartered in Brussels. In fact, the folks in Brussels are looking at a nation unable to form a government at all and teetering on the brink of splitting into the two logical nationalities — Flemish and Walloon — which language, religion, and custom divide more than unite.

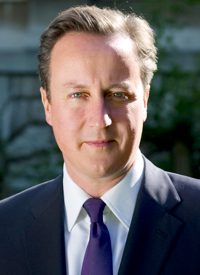

Prime Minister David Cameron (left) has a reputation as a technocrat and policy wonk rather than the tough leader of a clear political position. His coalition government with the Liberal Party (which is really the middle-of-the-road party in Britain) only makes that inclination toward a nuanced response to euroskeptics more politically natural.

The problem for Cameron is that significant members within his Conservative Party are demanding a popular referendum on British membership in the European Union. In parliamentary governments such as the United Kingdom, the head of government (Prime Minister Cameron) needs to have the confidence of a majority of the members in the lower chamber of the national legislature, or the House of Commons in Britain.

Many Conservative Party members want that referendum, but their leader, Cameron, does not. The two other major parties, Labour and Liberal, oppose the referendum as well, perhaps serving to becalm the boiling cauldron in Parliament and in the nation. Polls show that Britons overwhelmingly would support a referendum seeking to exit from the European Union. At least this means that, given the right resolution, Conservative backbenchers (less-senior members) could join with Labour and Liberal party members in a vote of no confidence in the Cameron government and the duty of Cameron, then, would be to call for a general election, which polls show his party would lose.

More than 100,000 signatures submitted by e-petition have been raised nationally to bring the resolution regarding a referendum to a vote and the move is now gaining real traction in the parliamentary process Today, 80 or 81 members of the Conservative Party opposed the government, ignored the party whips, and delivered the most decisive defeat to a British government since the United Kingdom joined the European Union.

Cameron has tried to sound sympathetic to the frustration of his backbenchers. He is also cracking the party whip, threatening that those who oppose his government may lose their jobs in government (for which they are paid salaries) and lose influence in party affairs. The Prime Minister is also telling Parliament that turning the nation’s back on Europe could have serious economic consequences for the region. Some Conservative MPs are rejecting that thinking. Philip Davies told the House of Commons in debate that the nation’s future lies with China, India, South America, and "…not being part of a backward-facing, inward-facing protection racket which is what the European Union is, propping up inefficient businesses and French farmers."

French President Nicolas Sarkozy, representing those French farmers, has told Cameron that he is "… sick of you criticizing us and telling us what to do." That prompted a Labour Party Miliband MP to observe in debate: "Apparently President Sarkozy, until recently his new best friend, had had enough of the posturing, the hectoring, the know-it-all ways. Mr. President, let me say, yesterday, you spoke not just for France but for Britain as well. We see a rerun of the old movie — an out of touch Tory [Conservative] party tearing itself apart over Europe. And all the time the British people are left to worry about their jobs and livelihoods. The prime minister should stop negotiating with his backbenchers and start fighting for the national interest."

Whatever the ultimate outcome of the parliamentary vote (which Cameron seems sure to win), or a backbench revolt in the future (which Cameron could lose), or an early general election on the issue of continued membership in the EU (which, give the strong support among Britons and the lack of support among the major political parties could yield a result no one can now predict — especially if the meltdown of the euro continues) this much is sure: There is no national consensus in Britain that it needs to be married to Brussels.

The centrifugal forces seem very strong now in the European Union. If the people of the United Kingdom want out, then the dissolution of the EU may not be far behind. It is ironic that Britain — which once held an empire covering one-quarter of the globe — should find so much of its political establishment wedded to the old idea of a United States of Europe. A very slight and nominal association, such as the British Commonwealth, has worked so much better.