Mohammed Sultan is a very successful businessman in India. He cherishes his daughter and so, when she recently married, Sultan decided to throw a big wedding for her guests. Five hundred people showed up and they were treated to a 30-course meal, which included Kashmiri dishes which reflect the rich culinary tradition of northern India. Who in the world could think that a man who worked hard his whole life did not have the right to treat his beloved child to a sumptuous wedding dinner? And when his guests had eaten all they wanted, Sultan threw what was left into the garbage, which prompted a controversy of sorts.

Apparently the government of India found problems with Sultan’s actions. Food Minister K.V. Thomas has said of these lavish weddings, “It’s a criminal waste.” Much of India is malnourished and much of the food at wedding banquets is simply thrown away. He has asked for a public awareness campaign to stress that more is less at wedding dinners. If this public awareness campaign fails, then Thomas has said that the next step would be setting a legal limit to the number of guests at a wedding. This would not be new in India. The government of Nehru in the early 1960s imposed a “Guest Control Order” to limit the number of guests at weddings.

Indian families affected by this are upset. Alka Gupta, the wife of a successful businessman who plans a big bash for her daughter’s December wedding, put it this way: “It’s my only daughter’s wedding. I don’t want to stint on anything and certainly not food. My husband and I have worked hard all these years. Now we want a spectacular celebration to invite all our friends.”

Distribution of leftovers to the poor have failed because many Indians, even hungry ones, do not want to eat other people’s leftovers and because food spoils quickly in India. The anger directed at rich parents who want to have big wedding feasts seems to be that this food could have been eaten by the poor and that it somehow reduces the amount of food available to the poor of India.

As usual, collectivists, led by envy and not reason, miss some important points. These big wedding banquets put much money directly back into the Indian economy, particularly helping those in the food service industry and the small farmers of India. Those Indians who fix the meals, serve the meals, even those who take the leftovers to the garbage receive wages from this work. The more such weddings there are, the higher the demand for these workers and so the higher their wage levels.

Families who give these feasts are producers of wealth in India. One of the honorable and proper reasons for working hard and getting rich — cultural traditionalists would maintain —is that when one’s children are married, parents can throw a big wedding party. Depriving parents of that right means that the incentive to create wealth in India diminishes.

These families, in many cases, pay a great deal in taxes to the Indian government. Forcing them artificially into a lower standard of living causes a diminished desire toward hard work, savings, and invention. Why work hard and take risks if the money earned cannot be spent? Curtailing the incentive to earn more reduces the revenue of the government so that there is less money for roads, public health, etc. Some rich Indians are also philanthropists. They already give to charities which help the poor (Parsees, for example, are some of the most generous philanthropists in the world). Surely some of these rich folks, if the state pressures them into austere weddings, will consider that they have already paid for helping the poor.

There is also the question of what, then, are the rich supposed to do with their money? If they built bigger houses, then the same envious people and socialist bureaucrats would sternly frown at conspicuous consumption. Should they buy more and fancier cars? Those sorts of expenditures would be permanent affronts to those who find all private wealth offensive. After a wedding feast, at least, everyone goes home and the wealth spent is gone.

Should the rich travel instead, as a way of using their wealth? If so, then wealthy Indian families will be taking their money out of India and spending it in malls in America or cafés in France. The people who are upset about big wedding dinners would find any expenditure by the rich as selfish, vain, excessive, and wrong. What these people really want is no rich people, or perhaps rich people who live like those little old ladies who die and then are discovered to have $10 million dollars (or 444 million rupees) in their mattress.

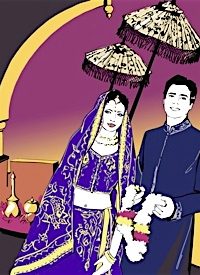

There is another aspect to this particular collectivist gripe that is undoubtedly troubling to people of many and varied cultural persuasions. The “Big Fat Wedding’ is a celebration. It is a celebration of family, that building block of all happy societies. It is a celebration of culture when there is a Greek wedding, or Jewish, Hindu, Polish, or Muslim, the true benefits of ethnicity flower. If this sort of celebration is discouraged, except in quiet and modest forms, then what is to stop collectivists from banning big Bar Mitzvah or birthday parties? Why, indeed, not huge family feasts at Thanksgiving or Christmas? If lavishness is a secular crime to collectivists, then why not restrict what can be done at funerals also? Ban all wakes, for example.

Is there a more honorable or decent reason to spend money than to celebrate milestones in life with family and friends, many would ask? These events reflect love, life and joy — and the overwhelming majority of people would surely prefer that they unfold without the state regulating and restricting these delights of human existence. Unlike a huge diamond ring that a woman may wear and is used only by her, these celebrations involve great sharing with others — they are a form of giving. And so, cultural traditionalists might ask: What really bothers collectivists? Maybe it is because private individuals and their families, not officious busybodies, are doing the giving. The rich who give big parties help the rest of us, until the green-eyed monster of envy whispers that their wealth comes at our expense. Collectivism, a garden variety anthropologist might observe, is simply envy using a politer term.