The U.S. Supreme Court next week will hear arguments in a case that may determine how far the government may go in detaining people as material witnesses. The court will hear a government appeal of a lower court decision upholding the right of Abdullah al-Kidd to sue former Attorney General John Ashcroft over Kidd’s arrest and detention in early 2003 as a material witness in the prosecution of a terrorism suspect. Kidd was detained for about two weeks as a witness against Sami Omar al-Hussayen, who was accused of using his computer skills to aid terrorists. A jury in Idaho acquitted Hussayen on that charge in 2004, but deadlocked on other minor counts. Hussayen agreed to be deported to avoid retrial on those lesser charges.

A U.S. native, Kidd is a former University of Idaho football player whose original name was Lavoni Kidd. He changed his name when he converted to Islam during his college days. He later became a music promoter and was involved with Hussayen in helping an Islamic charity in Idaho. The FBI questioned Kidd numerous times after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, but Kidd says he never was told he was to be a witness against Hussayen and was never told not to leave the country. Six months after his last meeting with FBI agents, he was arrested at Washington’ Dulles International Airport, where he was on his way to Saudi, Arabia, to pursue a doctorate in religious studies. A government affidavit said Kidd was “crucial to the prosecution” of Hussayen.

Kidd’s suit claims the government abused the material witness law, using it as a form of preventive detention, while investigating and trying to build a case against him. “They were scrambling to make a case against me,” Kidd said to the New York Times in an interview last week. The Times noted Monday that when FBI director Robert Mueller gave Congress a progress report in March of 2003 on the agency’s efforts in “identifying and dismantling terrorist networks,” he made prominent mention of the arrest of Kidd, who was being held at the time. But Mueller never mentioned that Kidd was arrested as a material witness, rather than a suspect. A provision of the USA Patriot Act, passed by Congress and signed by President George W. Bush after the 2001 terrorist attacks, allows the detention of terrorism suspects without charges, but the provision applies only to non-citizens and allows such detention for only seven days. The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution affirms the right of people to be secure “in their persons, houses papers and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures…”

Kidd also claims he was subject to harsh treatment, being made to sleep on the floor of his cell during his detention and having been shackled, strip-searched and forced to sit naked and shivering in a holding area in the presence of both male and female guards. Kidd settled lawsuits against his jailers over those claims, but the larger question of whether the federal government misused the material witness statute is the one to be argued before the Supreme Court. One of Kidd’s lawyers, Lee Gelernt of the American Civil Liberties Union, claims both the law and the detainee were abused.

“It is clear that the material witness statute was used as a tool for preventive detention and investigation, resulting in abuse and significant human hardship,” Gelernt told the Times. “The question now is whether lower-level officials will be forced to take all of the blame for following a policy adopted at the highest levels of the Justice Department.”

The Justice Department, representing the former attorney general, claims Ashcroft is entitled to immunity from a lawsuit based on actions he took in carrying out his prosecutorial duties. That argument was rejected by Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco.

“Some confidently assert that the government has the power to arrest and detain or restrict American citizens for months on end, in sometimes primitive conditions, not because there is evidence that they have committed a crime but merely because the government wishes to investigate them for possible wrongdoing,” Judge Milan D. Smith Jr. wrote in the 2-1 decision of a three-judge panel in 2009. “We find this to be repugnant to the Constitution and a painful reminder of some of the most ignominious chapters of our national history.”

The Justice Department contends Ashcroft complied with the requirements of the law and obtained a warrant for the arrest from a federal judge. In his brief to the Supreme Court, acting solicitor general Neal K. Katyal argued that upholding the circuit court ruling would effectively declare the material witness law unconstitutional in many cases and would open “every material witness warrant sought by a prosecutor to challenges based on claims that the prosecutor has an investigatory or security motive.”

The Supreme Court has scheduled the hearing for Wednesday, March 2.

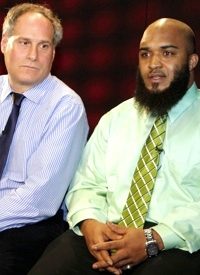

Photo: In this photo taken on Feb. 14, 2011, Plaintiff Abdullah al-Kidd, right, and his attorney, Lee Gelernt, talk about a Supreme Court lawsuit against former Attorney General John Ashcroft: AP Images