"So now we are beginning to hear murmurings about the possible invigorating effects of 'just a little inflation.' Perhaps 4 or 5 percent a year would be just the thing to deal with the overhang of debt and encourage the 'animal spirits' of business, or so the argument goes." Businesses will be encouraged to invest today in anticipation of higher prices tomorrow. A further weakening of the dollar would also boost exports, thereby spurring an economic recovery, some theorists have suggested, arguing that we can return to price stability as the economy expands again.

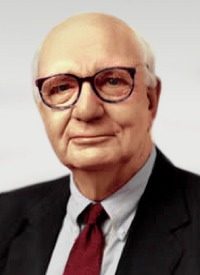

"Well, good luck," wrote Volcker, who was Fed chairman from 1979 to 1987. Recent economic history contradicts some "mathematical models" that may have been "spawned in academic seminars," he argued.

"I thought we learned that lesson in the 1970s," he wrote. "That's when the word stagflation was invented to describe a truly ugly combination of rising inflation and stunted growth." Volcker's warning might call to mind the perils of an addict looking for another high or a drunk trying to cure a hangover with "a hair of the hound" that bit him. The danger of trying to cure our economic maladies with "a little inflation," he warned, is in what will likely happen when "a little inflation doesn't work. Then the instinct will be do to a little more — a seemingly temporary and 'reasonable' 4 percent becomes 5, and then 6 and so on." The real risks far outweigh the imaginary benefits of following the "siren song" of curing economic stagnation with "a little inflation," Volcker said.

"At a time when foreign countries own trillions of our dollars, when we are dependent on borrowing still more abroad, and when the whole world counts on the dollar's maintaining its purchasing power, taking on the risks of deliberately promoting inflation would be simply irresponsible," he wrote.

But when would be a good time to promote inflation? The Federal Reserve has been inflating the currency at varying rates for nearly the whole time since it was established in 1913. While we have more dollars today, the purchasing power of the dollar is less than five percent of what it was in 1913. A dollar saved that year was worth less than 50 percent just seven years later, as the cost of living soared by 110 percent between 1913 and 1920, when the nation was in the midst of a depression second only in severity to the Great Depression of the 1930s. Following the stock market crash in 1929, the Federal Reserve pursued a ruinous deflationary policy from the end of 1929 to 1932, when prices plummeted at the rate of nine percent a year.

Instead of contributing to price stability, the Fed's interventions contributed to artificially induced price swings and destabilizing fluctuations in the marketplace, creating an economic climate of fear and uncertainty. More of the same occurred at the end of the past decade when the Fed held interest rates artificially low while expanding the money supply, creating an artificial bubble in the housing and financial markets. When the bubble burst, the large banks and financial companies lined up for federal bailout money and the rest of the country is still dealing with the effects of the recession that followed.

Congressman Ron Paul, who has called for an end to the Federal Reserve System, has pointed out that its manipulations of the money supply have sent false signals to investors by creating an illusory supply of capital, when in reality "that capital came from a computer at the Federal Reserve. Therefore it sent the wrong information to businesses and savers, claiming that there was a lot of savings out there. Based on that, people over-invested and built too many houses. It's the Federal Reserve that sends out the incorrect information," Paul said.

In a genuine free market, interest rates would be established through laws of supply and demand based on spending and savings decisions people make with their own money. Real economic stability would come from money based on commodities of lasting value, such as gold or silver, rather than on paper dollars, backed by nothing, and increased in quantity and supply according to the designs and calculations of economic czars in Washington, D.C. As historian Thomas E. Woods, Jr. wrote of the Fed in his 2010 bestseller, Rollback, "This alleged guardian of the dollar has actually been lowering the dollar's value. And this institution, supposedly a bulwark of capitalism, is in fact a central planning agency at odds with the basic principles of a free market."

Photo: Paul Volcker