Today, August 25, the predecessor of the brutal Chinese communist regime that grabbed power after World War II — the Kuomintang, or Chinese Nationalist Party — celebrates its 100th anniversary. But establishment organs rarely credit the Kuomintang for founding a system of governance in China vastly superior to what was to follow.

Marxists, following the same path described by George Orwell in his dystopian novel 1984, are constantly in the business of rewriting history to make those who governed before them seem worse than themselves. Conditions in Tsarist Russia, for example, have been uniformly portrayed by Marxist-leaning academicians as appalling, and the Bolsheviks are then credited with “at least” providing free education, ending class barriers, taking land away from the nobility, and so forth.

As former-Marxist Eugene Lyons painstakingly revealed in his magisterial Workers Paradise Lost, published in 1967 on the 50th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, in every measurable area of life, Russians, Ukrainians, White Russians, and other peoples in the Russian Empire were far better off before than they were under the Bolsheviks.

Tsarist Russia was a major leader in global technology, with a quickly rising literacy rate and artistic and literary achievements that dwarfed anything that the Bolsheviks accomplished. Russian jurisprudence under the Tsars was not only far better than anything under Lenin or his successors, but it compared favorably with any legal system in the world. Industrial production was increasing at the rate of 10 percent per year.

Marxism changed all that. The Ukrainian breadbasket in 15 years became the charnel house of the world, filled with starving babies abandoned by parents, and cannibal gangs who desperately roamed in the night in search of anything to eat. Soviet science was a mockery of true science, filled with charlatans such as Trofim Lysenko. The great literary tradition of Russia survived, but only because dissidents such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (Gulag Archipelago and other books) and Boris Pasternak (Dr. Zhivago) wrote about the flaws in this Marxist paradise.

A few years ago Cubans “celebrated” the 50th anniversary of Castro’s seizure of power. But there was little to celebrate. People are still risking their lives to leave that benighted, poverty-ridden country. But Castro, it is said, at least got rid of Batista, the notional monster who sold his nation to the mob.

Reality is very different. The standard of living in Cuba under Batista was, in many ways, higher than any other Latin American nation or indeed most nations in Western Europe. Opposition newspapers and radio stations flourished, infant mortality rates were low, and literacy rates were among the highest in the world.

Which brings us to China. Today, the predecessor of another Marxist regime celebrates its 100th anniversary.The Kuomintang, or Chinese Nationalist Party in China, has uniformly been given a bad reputation in academic communities and its members are invariably portrayed in films or novels as “corrupt” and “incompetent gangsters.” The Kuomintang, or “Party of the People,” was certainly imperfect, but then so are all political parties and all governments. A more pertinent question is how does the Party of the People stack up against other Chinese governments?

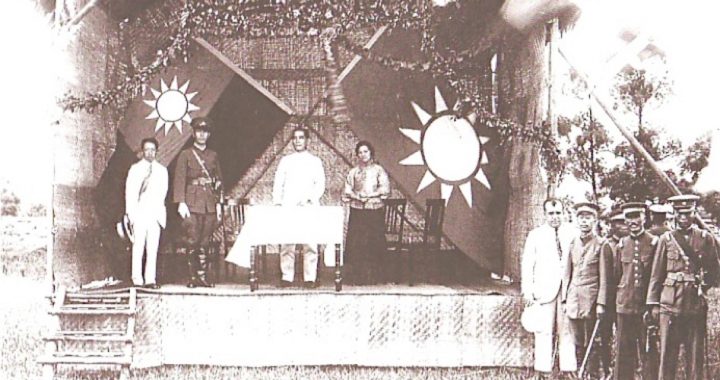

The Manchu Dynasty and the Dowager Empress were typical of any oriental despotism. Although not unusually barbaric or backward, this hoary system did not serve the Chinese people well. When Dr. Sun Yat-Sen and his party replaced this old empire in 1912, nearly everyone saw this as positive.

What came after the Kuomintang, however, was truly horrific. Mao Tse-tung invaded Tibet and began his campaign of genocide against the Tibetan people, while Chiang Kai-shek had largely left Tibet alone. Mao created a totalitarian police state in which no one was safe. His “Great Leap Forward” included such wildly impractical ideas as backyard steel furnaces and campaigns requiring Chinese subjects to turn in a specific number of insects each day. (The consequences of that idea were a black market in dead insects and the near-extermination of a number of bird species which had been artificially deprived of their food.)

Mao also launched his campaign to “Let 100 Flowers Bloom,” which resulted in his critics opening their mouths and then finding themselves arrested, tortured, and sent to prison camps. Mao’s “Cultural Revolution” encouraged students to terrorize every part of Chinese life, after which they, in turn, became victims themselves.

Would China have been better if the Kuomintang ruled instead of the Marxists? One easy answer has been the comparison of Free China (the Republic of China on Taiwan) and Communist China (the People’s Republic of China on the mainland). Taiwan was something of a backwater until the Kuomintang made the island their Chinese Republic after the end of the Chinese Civil War. The standard of living in Taiwan is about $37,000 per year today, compared with Red China’s per capita income of about $8,000 per year.The political and civil rights of citizens of Free China are also far greater than in Communist China.

Perhaps the most revealing analysis of the Kuomintang and the Red Chinese is explained in a 2008 book by Professor Frank Dikotter, The Age of Openness, in which he examines the governance of China (including local government) under the Kuomintang, the ease of entering or leaving China at that time, the academic and artistic freedomenjoyed by ordinary Chinese (and the remarkable achievements that they made during these decades), and the free markets in China (with corresponding levels of economic growth).

Professor Dikotter points out again and again how the Chinese people, under the light hand of the Kuomintang, rapidly advanced in countless areas to a degree which is absent not only under Mao but also under his Marxist successors. During happier times, more than 100,000 books were published in virtually every field of human knowledge and thought. Advanced scientific periodicals such as the Astrophysical Journal were read throughout China (indeed, China was the sixth largest subscriber to that journal in the world).

China, then, had some of the finest physicists in the world, including two who would later (at the University of Chicago) earn the Nobel Prize for physics, as well as the first female physics instructor at Princeton. But it was the ordinary education for the lowliest peasants in the most distant villages that stunned foreign visitors by the level of development in a nation which they had thought was hopelessly backward.

Missionaries, Protestant and Catholic, established countless schools, orphanages, hospitals, and colleges in Kuomintang China, where they were welcomed. All religions breathed fresh air in this China, and synagogues, mosques, and Buddhist temples flourished as well.

The Kuomintang, whose 100th birthday is celebrated today, ought to receive the respectful attention that it deserves. It was not a panacea for all the problems that a vast land such as China faced. But it let the Chinese people themselves enjoy the potent tonic of liberty.

Photo: Sun Yat-sen [middle] and Chiang Kai-shek [on stage in uniform] at the founding of the Whampoa Military Academy in 1924.